Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

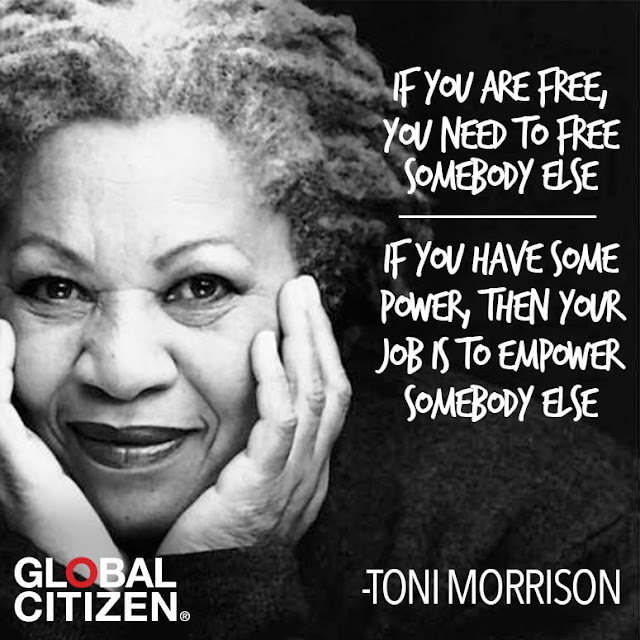

Toni Morrison – Mentor and Muse

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 8 minutes

- Article

Share

Out of the blue a friend asked if I knew Toni Morris – yes- they’d omitted the suffix ‘son’. So I said, ‘no, Toni Morrison, not Morris’. ‘Yes, sorry, Morrison – a writer. She has died.’ I was in Guyana at the time and felt my heart racing as I tried not to believe it. Perhaps because of the circumstance of hearing the news – by someone who had no idea who Toni Morrison was but was reading the headlines on the TV and thought the ‘news’ might interest me, I found myself trying to control my shock. Tears too, I held back. But I had to go online myself to check that it was real. And I don’t know how I can do honour to this force I’ve held in such esteem since I was initiated into her sphere of literary genius as an undergraduate so many years ago – but I’ll see how well I ride.

Like many of us initiates and students of Morrison it started with The Bluest Eye. This was a relatively late discovery for me, as I’d been deprived of any African/Black literature at school and only by chance landed in the lap of Morrison. The Bluest Eye was like a magical canvass on which everything I felt about myself and the people around me were richly laid out. All the characters were deeply familiar – remarkably brought to life in a way I could relate to and had never before been able to in other literary works. The exception I think was James Baldwin’s characters in Go Tell It On The Mountain, but there is a mental blurring about which of these two I read first. Baldwin too was discovered by chance – which initiation I equally cherish. By familiar I mean exactly that I recognised them from memories and experiences of Guyana and London. I knew them intimately and this was so because Toni, as Mentor and Muse had magnificently pierced my consciousness and opened me to myself, my interior world. This world was both individual, collective and conscientiously African and with it I intuitively identified.

It was therefore initiation and (re)birth. It would remind me that I used to write, once upon a long ago. But I had put writing aside, toying with awful poetry but not the longer pieces I used to try as a teenager. The discovery of Morrison (and other African writers at that time) lead me to change my Undergraduate from Business and Finance to English With Commonwealth Literature. It was around this time too (1992/3) I came upon Daughters of Africa, which was another enchanting tool of liberation for me as a student of literature and later writer (at that time I had no desire to become a writer). Rather what I didn’t fully realise was how impacting this period and my musings with Morrison would be. I knew, however, that something was opening up for me and these African writers, with Morrison leading had a lot to do with that.

The book was on the exam paper at my university (Stirling, Scotland). We had to do a reading and give a critique of a passage. I chose the one where Pauline Breedlove (Pecola’s mother) is one day visited at her workplace (as a domestic for the white family with the ‘Shirley Temple’ blond pony-tailed daughter) by Pecola and her friends (I think!). She is going down some stairs (as I recall), she had made blue berry pie, which dramatically drops, splattering on the floor, its hot berries burning Pecola. Pauline is vexed, the berries has spilled a bit on the white child’s dress – she was also in the scene. She gently soothes and tends to the white child and pushes her own daughter down into the berry juice, chastising her for causing the pie to drop. Her soothing of the white child contrasts her cold admonishing of her own daughter – exacerbating the latter’s (the story’s protagonist) self-hatred and later madness as she longs for the glassy blue eyes out of which the world would look and be somewhat prettier and better.

I interpreted this scene as follows: Pauline descending stairs expresses a psychic descension in terms of her own long standing self-hatred. The splattered blackish blueberries reflect the impression/sense of black dirtiness/mess and ugliness that Pauline is psychically suffering from and transferred to her daughter. I noted that the black blueberries starkly contrasted the sparkling whiteness of the floor and also the Shirley Temple child in its false perfection so envied and longed for by mother and daughter. The descent and spilling of the pie foregrounded (as did so many motifs) Pecola’s demise – not only hers but the family’s – microscopically representing the black family who generally bear this blightful burden of ugliness/inferiorisation. I wrote words similar to those anyway – because it was real to me and deep. When my exam paper returned it was given a poor mark – with the teacher’s comment – ‘I think you’re reading too much into this!’

That didn’t deter me from knowing what I knew. In fact, I knew too that that teacher/examiner could mean what she wrote, just be mean, or could just not see what I could. She was white of course, though that doesn’t mean she could never see this basic reading as I saw it. After all what was involved in literary criticism but to try to interpret the words the writer has so skilfully mapped for the reader to discover, eloquently or not. For me this comment meant that I would have a special and private relationship with Toni Morrison that no one could tell me was not real. Toni had worked those words of her first book so well they had etched themselves kinetically into my being and made her my muse long before I realised I needed one (or many). With her passing that relationship is cemented.

I would later have the chance to read more of her works as a student, for my postgraduate studies and then to teach her. Before this, however, I had a dream of Toni Morrison. I was now at University of North London, midway through my Masters. I don’t know where we were, but let’s say we’re in dreamspace somewhere. Ah yes, it was a room, as though we were sleeping over somewhere. Toni was asleep beside me. Jean Stubbs, then Director of Caribbean Studies Centre was alert in contrast and I was awake listening to her saying some academic stuff I can’t remember now. That’s all I recall. When I told my supervisor, she said something like ‘your creative/writer side is asleep and your other academic side is at work/functioning’. I’m paraphrasing from memory but the sentiment never left me. Years later it would drive me to publish my first books. Yes, I cut to the literal chase of rejections and decided to self-publish, after I had shunned doing so for years – and still have angst about it but it is what it is. My supervisor, another wonderful mentor – Dr Patricia Murray was always supportive and reminded me that I had the resources of Morrison and others whose brilliant literary works could be drawn upon to develop my own writing. Advice I continue to live by. It was she too, my supervisor, that sparked the idea to do an independent course introducing Toni Morrison as we’ve been doing with the Amazing James Baldwin courses to a new generation of students/readers. It’s coming…though Zora beckons too.

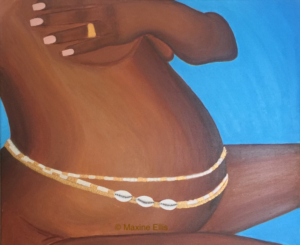

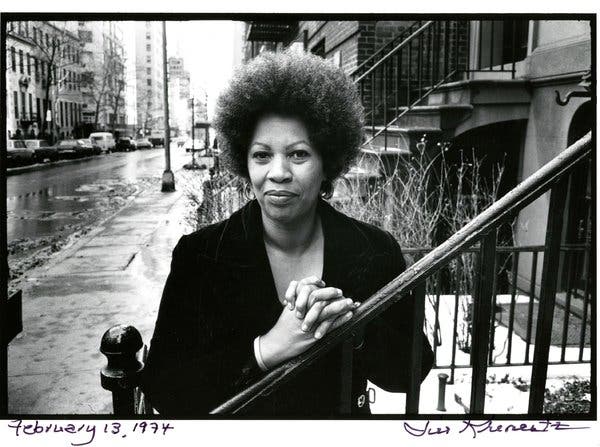

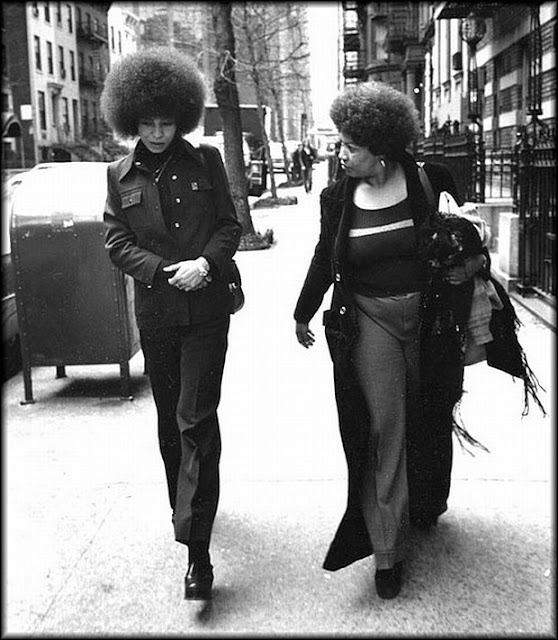

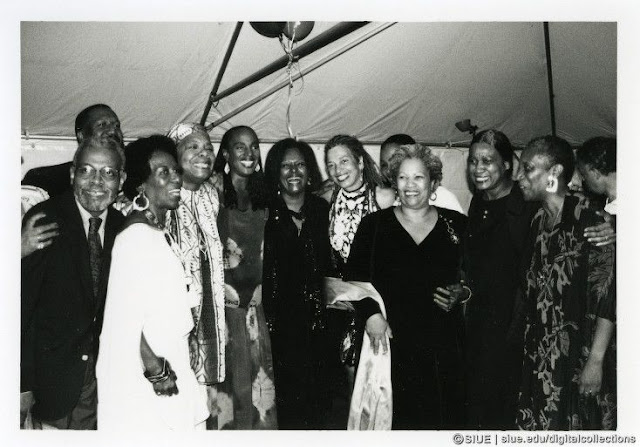

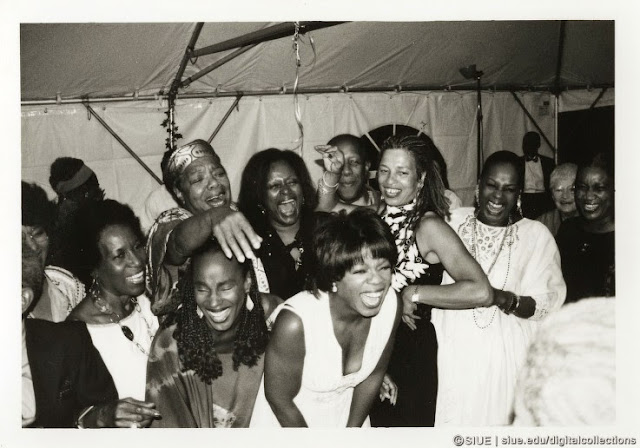

Toni Morrison is dancing off camera as she and friends celebrate her Nobel Prize win

While my fellow students and later those I taught struggled to read Beloved this remains one of my favourite of her books because it gave me the same sensation I had when I first read The Bluest Eye. It is one of intimacy, of consciousness and the way her words push one to expand not refract. With Beloved, particularly, it was the memorialisation to the ancestors and the way she created this literary monument to them. For me, the connection with Morrison was also because her writings have that quality of spiritual possession, of being expressed through a kind of trance state that her clinical editing skills evoke so magnificently. When I read or heard her remind us that the novel means new reading her books became almost sacred, certainly spiritual. It would be this assertion of the newness of the ‘novel’ that inspired me to write the way I have. Thus for example my novella Something Buried in the Yard would be thought ‘experimental’ but for me is natural. It reflects the aesthetic Wilson Harris spoke about in urging Caribbean Writers to write out of our consciousness, to avoid mimicking the dominant styles that have been imposed on us. Naturally, great literature and art must be given due credit and appreciation but Harris, Morrison, Baldwin and others being great themselves challenged the prevailing hegemony of Western literature atop of which stood mostly white men and women.

On my return from Guyana, I became more conscious of the impact of Morrison’s passing – on the world, on me. She was a force, like Maya Angelou whose spirit in the flesh was vitally grounding. When such forces are no longer there physically it feels like a lonely shadow has taken their place. I was ‘feeling’ Toni, in my being – feeling that she had so long been part of my consciousness I didn’t want to believe she was gone. And then the magic happened to snap me out of the impending melancholia. Morrison, like Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Jessica Huntley among many others is now an ancestor. Her rainbow appeared to remind me of this cosmic relationship on the day we’d just returned from doing an opening to spirit ritual for the Orisa Osun. We had prayed there would be no rain. That downpour held up until we had landed back home – then I saw that enchanting sun and rain dance and knew to look out for the rainbow. I was screaming into the sky, the rain tapping my face, the sun warming it that it is Toni’s rainbow. It is Toni Morrison’s rainbow. And so my skin got that tingly feeling and I could see her in my mind’s eye and feel her in my spirit. And so I look forward to the expansion she will bring to us all from that ancestral base. I know she will be like Marcus Mosiah Garvey reigning as a beautiful kind of terror tirelessly targeting the elevation of African peoples who have too long been denied our humanity and our dignity. Her words will continue to have power and vital meaning for us, as we give blessed thanks that she was writing all this while, as she said, for us in the same way Tolstoy was not writing for us. I am grateful and feel beyond blessed to have Toni Morrison too as a most magnificent muse.