Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

#BlackBoyJoyGone & Displaced: Creative Ways for Black Men to Heal: By Michelle Asantewa

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 4 minutes

- Article

Share

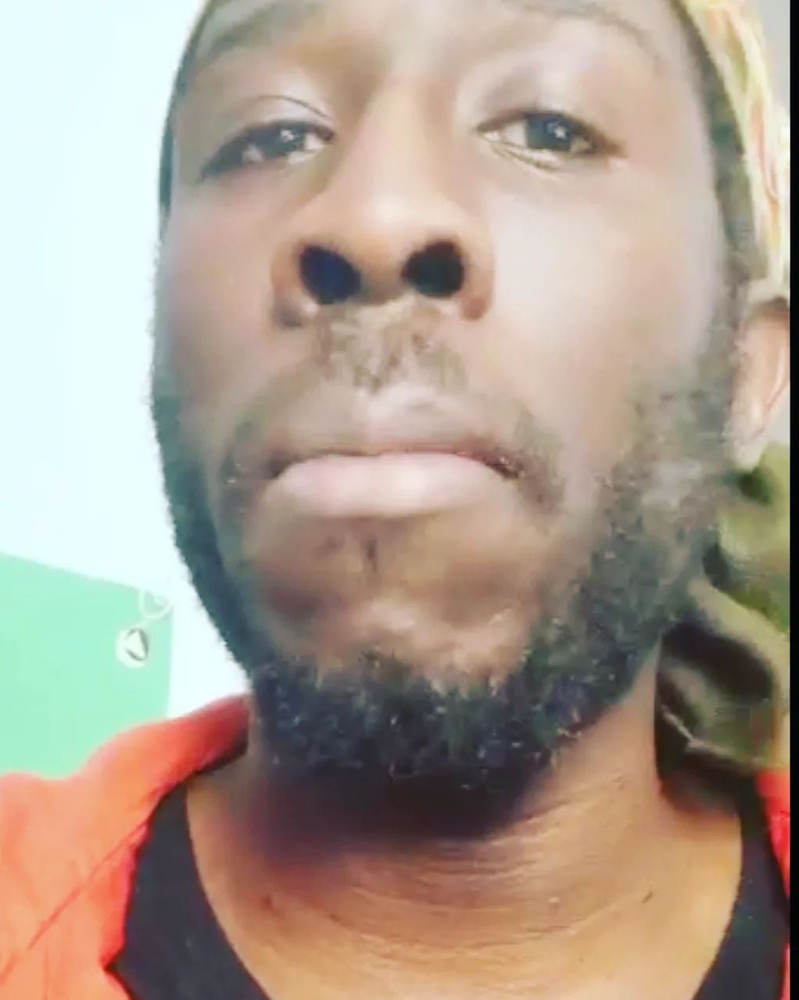

A few weeks ago, a video of a young African man describing his experience on a mental health ward at Queen Mary’s hospital surfaced on…

A few weeks ago, a video of a young African man describing his experience on a mental health ward at Queen Mary's hospital surfaced on social media. He described the power held by the senior consultant in charge of his ‘care’ (or residency?). Being in position to decide his fate, she wished for him to take injections every two to four weeks as conditions of his release back into the community. He said he disagreed with injections and refused to take them. The consultant also said she felt intimidated by him, which he interpreted as a classic stereotyping of black men’s aggression and white female fragility. Having visited this young man at the hospital, I could see he is on a journey, as we all are, and needs to be in a more harmonious environment that is centred on meaningfully helping him to fully restore his health. These so called ‘hospitals’ are built like semi prisons to lock away individuals, dose them on medication, often for life without giving consideration to potential holistic practices that would complement or serve as alternative to these medications. His case continues, but I use it here to pose its parallel with two short films I saw last week that deal with issues around black men’s mental health – ‘#BlackBoyJoyGone’ and ‘Displaced’, screened at Streatham Space on May 11th. Both films, described as ‘unique visual productions,’ explore mental health and the related, if not consequential, experiences of race, identity, trauma, and the power of overcoming.

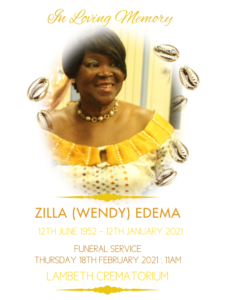

Akadi Sankofa, from his post in April about his mental health experience at Queen Mary's hospital.

We saw the longer film ‘Displacement’ first, which starred Akeim Toussaint Buck, and was co- directed by himself and Ashley Karrell. It positioned Akeim as a central character negotiating various experiences and scenes of displacement. In one moment, he was on a beach, bare chested, and barefooted in what must have been icy climate somewhere in the North of England. His body was painted to reflect tribal markings of an African past or perhaps an African priest/shaman. Instances of displacement such as the scene in a church where revivalist singers performed an uplifting chant accompanied by shoulder shaking drum beats caught the audience somewhat off our guard. The effect was to invite us to reflect on our own experiences of displacement; that it is something lived daily, often without our awareness.

Slavery, colonialism and European imperialism were referenced, albeit a little too much for me, as conduits of the unending burden of displacement. Akeim related its unbroken chain of history through his compelling dance movements interwoven throughout the narrative.

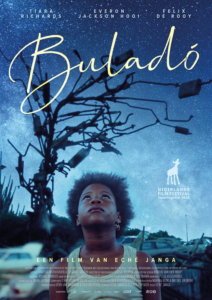

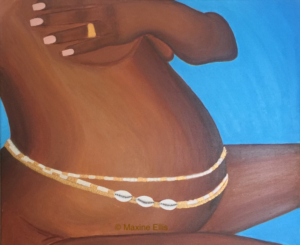

The shorter film ‘#BlackBoyJoyGone’ starred Issac Ouro Gnao and was also co-directed by himself and Ashley Karrell. It incorporated magical realism and dance to dramatically convey Issac’s personal narrative of trauma and healing. Raw and evocative, with snatches of liminal scenes, this docudrama provided a dynamic insight into black men's responses to their mental health issues. I loved that they were mostly young black men, but an elder gentleman also shared his experiences and the strategies he used for overcoming. One young man related that he had to ensure he started his day with a positive note to himself, which charged him with power to complete his activities, not only for himself, but for others in his community. Issac shared his trauma of sexual abuse and used African spirituality as well as his creativity as sources of healing. Iconic deities like Mami Wata, Ogun and Shango were shown through a series of vignettes that involved dance sequences; his narrative forming the foundation around which the other men’s stories were centred.

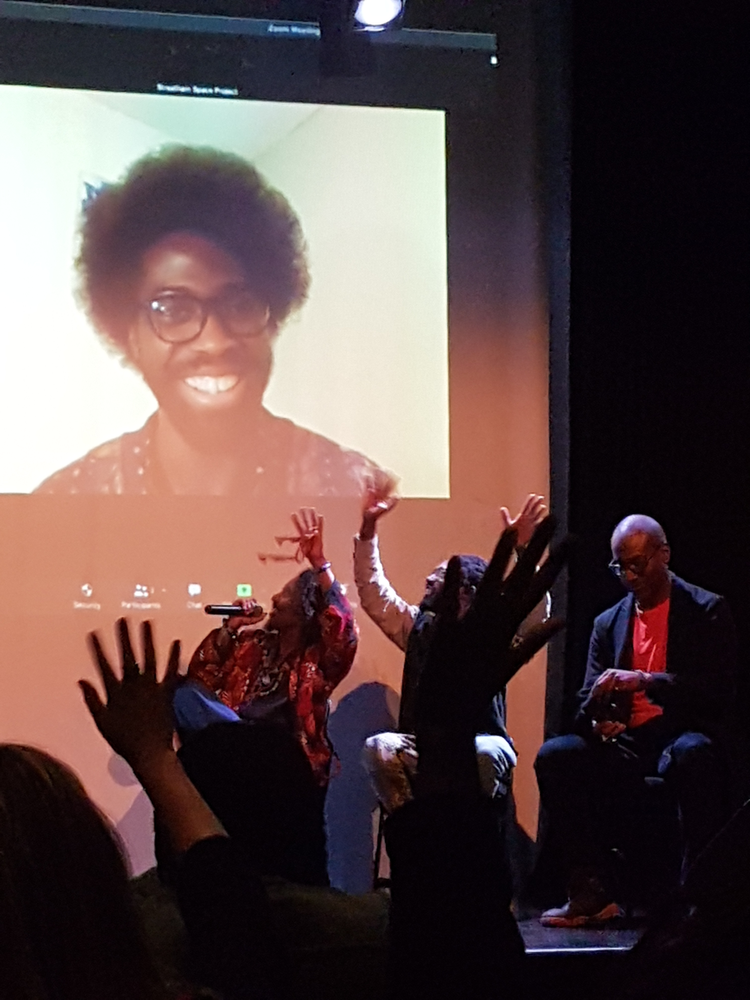

Audience waving at Issac, with Muti, Akeim and Ashley on stage for the Q&A

Both films were produced by Ashley Karrell, but it was clear these were collaborative, creative projects. The artists are also activists involved in a movement of transformation and affirm that they are a generation of changemakers. Although it wasn't explicitly highlighted in either piece, I think their approach revealed that their work also challenges the displacement of masculinity, especially as Isaac noted during the Q&A that his use of African deities was not intended to be binary. In other words, African deities were expressed as either gender and can be claimed by anyone.

Muti of village 101 who facilitated the Q&A gave the audience the opportunity to share their own experiences and responses to mental health and to identify where they had used their creativity for transformational healing. This was a welcome initiative as the audience enthusiastically celebrated the power of both pieces which they observed were strikingly familiar and relatable, though they were given a unique creative lens to be explored.

The parallels with the young man with whom I opened this piece are fundamental, particularly as he is also a creative, on a journey of self-discovery, of trying to find the source of his healing and transformation. The difference is that he is currently fighting with the beast of a system that wants to deny him the freedom to explore his own methods of healing. As both films showcase there can be other ways to heal. The engagement with nature, beautifully resonant in the opening scenes of ‘#BlackBoyJoyGone’ where colourful flowers bedazzled our senses, cannot be overstated as a remedy towards this healing process.

‘#BlackBoyJoyGone’ is up for an award at Cannes this year – it is truly deserving. Both films deserve to be shown at larger theatres for a deeper engagement with the very topical themes and issues they raise.

Ashley Karrell welcomes audience at Streatham Space for the film screening.