Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

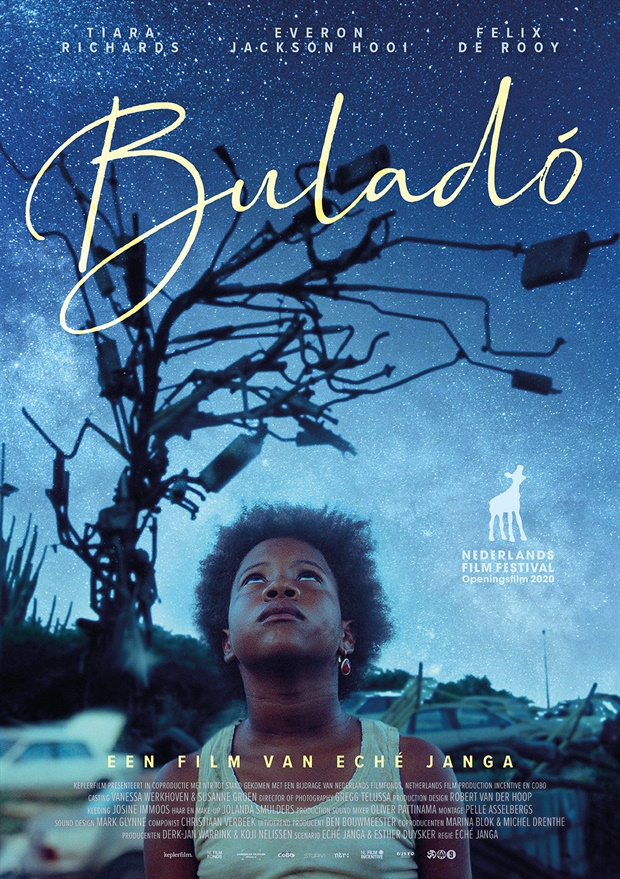

Buladó: A Review of the BFI preview on Saturday 27th of November

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 4 minutes

- Article

Share

At one of the Opening to Spirit Rituals to Mami Osun, a friend was urging me to speed it up. He was concerned that the attendees, a…

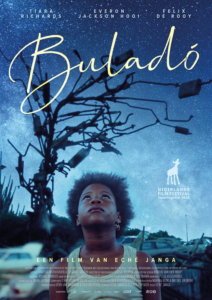

At one of the Opening to Spirit Rituals to Mami Osun, a friend was urging me to speed it up. He was concerned that the attendees, a number of them new to the annual ritual, would become bored, impatient and grumble about the “event.” As gently as I could, I asked him not to rush me or rush it – the process. Experience has taught me that in any matter of spirit and working with ancestors, patience, timeliness, and divine order are paramount. This doesn't mean the occasion should drag, but it must be done to the satisfaction of the spirits to ensure the manifestation of an outcome that is super intelligent. The opening scenes of Buladó (2020), though beautiful and somewhat celestial reminded me of the pace of that ritual my friend was urging me to speed up. I went with my niece and her partner to the BFI’s preview of director Eché Janga’s second film on Saturday 27th November. It was introduced by David Somerset to a woefully small audience. I wondered if my niece and partner were feeling the same about the slow beginning. They would later confirm that at first, they thought it was but then –magic happened.

Despite its relatively low-key exposure Buladó won the Golden Calf for Best Feature Film, last October, at the Netherlands Film Festival, where it premiered. It was also selected, but not nominated as the Dutch entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 93rd Academy Awards. It is the first film I have seen from Curaçao and it will remain with me for that and for the enchanting ways it incorporated indigenous spiritual practices. This film elevates ancestral veneration from an area of the Caribbean we rarely get to see on screen, let alone engaging with spirituality the way we’re familiar with from the Anglophone and Hispanic ex-colonies.

Director and co-writer (with Esther Duysker), Eché Janga

It tells the story of Kenza (Tiara Richards), her father Ouira (Everton Jackson Hooi) and grandfather Weljo (Felix De Rooy) who must negotiate their differing ideas about spirituality. For 11 year-old Kenza it’s very much about coming into her own spiritual awareness as well as adulthood. Although she had never acted before, Tiara’s presence on screen assumes the gift of natural talent and the kind of sensitivity Janga says he was seeking when they scouted for a young girl to play the part. “She had to resemble my sister,” he says (cited in the BFI programme notes). This was because Buladó, 12 years in the making, was about Janga’s own family.

The three central characters are locked in an intergenerational battle of wills that depends, not only on their respective interpretation of spirituality, but also history, cultural identity and economic status. Underscoring their different and conflicting views about spirituality is the emotional trauma borne by the loss of Kenza’s mother, Ouira’s wife, for which he is still deeply in mourning. Having never met her mother, Kenza’s yearning for her is both catalytic and cathartic; providing an opening, on her terms and determination, to spirituality and maturity.

Everton Jackson Hooi

The film covers a range of material realities without overextending any one of them. Each are accorded special notice, allowing the viewer to see them rather than be didactically drilled about their significance. The National Museum, with its cultural artefacts, for example, conveys the historical pillaging of colonisers, and where the spirited grandfather desires to retrieve the loot that he knows belong to his people. There is a rusted ship along the coast, artfully situated to show, rather than tell, of the transatlantic slavery. The showing over telling, Janga says, is deliberate and linked to the culture of Curaçao. “The less dialogue for me, the stronger the image and this is the reason why I always use not so much dialogue and I tell my story with images and looks of people and how they behave,” (BFI notes). So naturally when words come during the film, they are indeed “heavy” and “meaningful.” A powerful instance of this is when Kenza, in one of many outbursts at her father, tells him to go back to Holland. “You're such a white man.” Instead of the local Papiamento language, he insists she speaks Dutch, deeming this to be aspirational for a better life. Contrarily, her grandfather, whom Kenza adores, speaks to her in their language and inculcates her into their spiritual traditions. Her grandfather sees her as a brave young warrior, much like her mother, and wants her to understand the way of the spirits and ancestors, but her wilfulness means she must come to this understanding for herself.

Felix De Rooy and Tiara Richards