Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

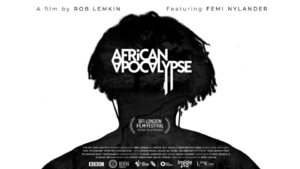

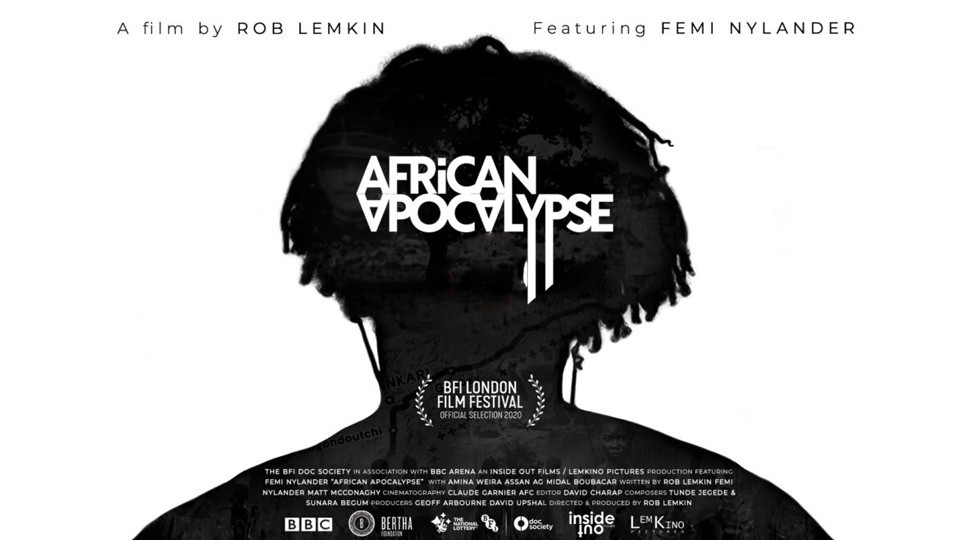

Dr Ama Biney’s REVIEW OF THE FILM “AFRICAN APOCALYPSE” by Rob Lemkin (Dir.), narrator, Femi Nylander

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 4 minutes

- Article

Share

The colonial conquest of Africa, or the scramble for Africa was sheer violence inflicted on African bodies, minds and land. The new film…

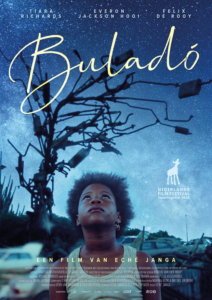

The colonial conquest of Africa, or the scramble for Africa was sheer violence inflicted on African bodies, minds and land. The new film entitled “African Apocalypse”, directed by Rob Lemkin and narrated by Femi Nylander is released in the UK at the end of October 2020 and in Africa, Europe and the USA in 2021. It illustrates not only the genocidal mission of the French Captain Paul Voulet in Niger in 1898-99, but innovatively parallels that mission alongside excerpts of Joseph Conrad’s novel, Heart of Darkness. The fictional character of Kurtz in the novel is juxtaposed against the historical reality of Voulet’s real life pillage, plunder and massacre in Niger. Voulet “was to embark on a mission of pacification and avoid angering the natives” in his unification of France’s scattered colonies in to “French West Africa.” The reality is that he mercilessly killed the natives in his sojourn across their territory. The focus of the documentary is the pursuit of the trail of conquest embarked on by Voulet, which is enacted by Nylander in a long journey in what is now the national highway in Niger. Med Hondo’s equally brilliant 1987 film titled “Sarrounia,”was

the African queen that fought the French in Niger. It vividly portrayed the moral depravity and bloodthirsty nature of Voulet and his mission based on historical sources.

The bottom up approach to history via the voices and comments of the ordinary people of Niger shows us the value of oral history and especially the importance of the African proverb: “Until the lion tells his or her side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” The villagers of Niger not only express clearly, poignantly but eloquently their views on Voulet; the French invasion of their land; the killing of their great grandparents as well as their profound belief that their present economic impoverishment is inextricably linked to their colonial exploitation. Interspersed in the documentary is the use of primary sources of official reports that give an insight to the French colonial agenda and that of Voulet and his colleague Colonel Klobb in 1899.

Historical context is needed to understand the colonial ambitions of France. Specific to France was the fact that the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 had led to a humiliating defeat. Moreover, it had led to the territorial loss of the rich iron-deposits of Alsace-Lorraine to Prussia. Consequently, France sought to retore her national glory and acquisition of overseas colonies in Africa and Asia which compensated for this profound national disgrace. Tiny Belgian and its King Leopold II also considered that it could not be great without an empire and referred to Africa as that “magnificent African cake.” Before 1880, France had hardly made any inroads into the hinterland of the colony of Senegal, yet by 1900 had occupied huge swathes of the Sahel in what was to become “French West Africa” or “Franque Afrique.”

The causes of the scramble for Africa remain contested among quarrelsome academics but nationalist ambitions and a desire to economically exploit Africa were underpinned by racist ideological ideas that Africans were in need of the three “Cs” – Commerce, Civilisation, Christianity. Hence, prior to the colonial violence of Voulet, European explorers such as Rene Caille, the French explorer, along with other European explorers such as Mungo Park, and R and J. Lander all played a critical role in relaying information from their travels on what they found in Africa, to European governments and traders.

Among the highlights of the film are a visit to the local archive by Nylander who listens to a tape recording of a 97-year old woman who had been captured for three months by Voulet. History comes alive as the woman narrates the atrocities she witnessed and experienced under Voulet. Another highlight is when Nylander is questioned by his guides on his seeming lack of emotion and one sees that the Eurocentric bourgeois definition of history as “objective”, “impartial” and “neutral” conceals the fact that sometimes a revelation or disclosure of great knowledge or events, requires that we have to take sides in judging history, for a refusal to do so is denialism and wholly immoral since history profoundly impacts human beings. Legacies are left by the historical events and processes of the past. Yet, another myth lies in the Eurocentric refusal to accept that many of Africa’s current problems have their roots in the colonial past. The film reveals that up until 2014 Niger was forced to supply France with uranium tax free. In doing so, Nigerians who worked in the uranium mines did so in exploitative conditions and often at great costs to their health. One man lost a kidney due to working in such unhealthy conditions. In short, as William Faulkner once said: “The past is never dead. It is not even past.”

Inspiring facets of the film are in the fact that Niger may be presented as the world’s least developed country, yet its people are engaging with renewable energy in solar power. Another positive lies in the fact that the children of Niger learn about the colonial atrocities of the French. The admirable eloquence of the school children and many of the participants in this film, reveals that Africans have honoured the duty to never forget what happened to our ancestors. On the whole most of the speakers are male – which reflects the patriarchal character of Niger’s society – for there are very few female speakers who speak alongside the female school children. It is also admirable that a new generation of Nigeriens speak of reparations for such crimes and that if Voulet were alive today he would be tried at the International Court in the Hague.

So much of Africa’s history remains to be told in ways that engage our people and make them centre stage, as this film succeeds in doing.

Dr Ama Biney is a historian and political scientist based in London. She can be contacted at: ama@fahamu.org