Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

Guyana Speaks 1: Yesterday and Today: ole time story by Eric Huntley

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 19 minutes

- Article

Share

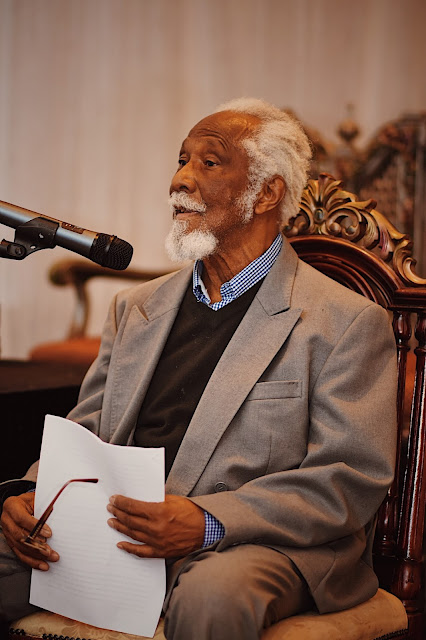

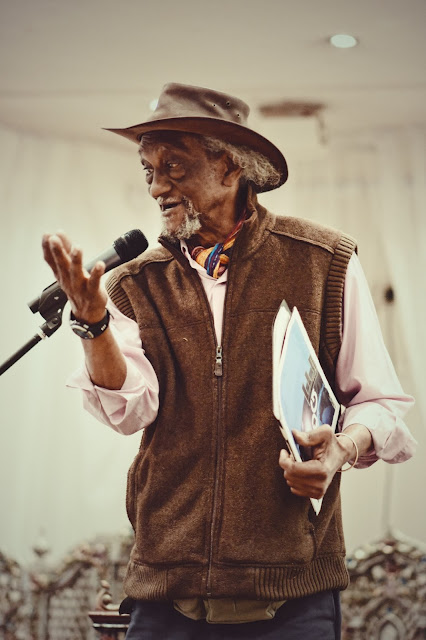

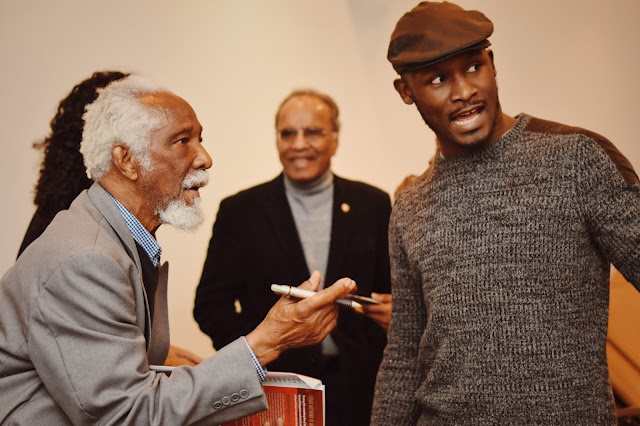

In this shout, I’m sharing the enchanting memory lane – ole time story – reading presented by Eric Huntley (with his courtesy).The Shout is interspersed with photos taken by Eddie Osei who so beautifully captured the spirit of the occasion at this first ‘Guyana Speaks.’ Thanks to Ra Hendricks, Tafawa Ntune, Juanita Cox-Westmaas and Rod Westmaas for sterling efforts organising. Speakers along with Eric Huntley were Marc Matthews (sharing his biographic ‘yesterday’) and Freelance Journalist Carinya Sharples sharing her impressions of Guyana, especially as relates to young people of today. We were also treated with inspired comments from the floor from Joyce Trotman, particularly on the question of there being a commitment to teach Creole (Guyanese) in our schools, and in truth recognising our bi-lingual position (increasingly multi-lingual given our Portuguese and Spanish neighbours).Enjoy!

Eric Huntley

Lecture for “Guyana Speaks – Guyana, Yesterday & Today”

My brief today is to speak about what is known about the term “ole time story”. There is a ditty which goes like this: “Every time I remember ole time story, water comma meh eye.”

Now, I imagine that listeners would expect some social commentary to be contained in the stories which would have been shared by many of the same generation.

Many of the memories also border on one’s living experiences which may or may not have any social content. However, I look forward to the sharing of memories with those who may have had similar experiences while at the same time shedding some light on the mores and practices which have contributed towards making all of us who we are today.

One of the features of growing up during the 1930s was that the decade was influenced by economic depression which made thousands of able-bodied men unemployed. At this time, breaking stones along the road-side with an old umbrella for shade from the elements may have been preferable to being unemployed.

Later, the Second World War had a most profound effect on all aspects of our lives. It also improved the prospects of employment while at the same time the importation of many goods was interrupted. The result was that we had to rely more on our own resources.

Tradesmen and women made and repaired many of the necessities for our daily lives. Seamstresses, of whom my Aunt Syny was one, made dresses and hats. Tailors made suits; tinsmiths soldered not only the guttering of roofs but also cups and pots. Bicycles were repaired and also rented, umbrellas were repaired, shoe makers both repaired and made the footwear. Many baked their own bread, reared their own poultry and fishermen made their own boats. At this point, I need not only to pay tribute to the skills of men and women who spent many hours sewing, but also to the Singer Sewing machine which perhaps is the single most important tool which helped transform many a life.

The list is endless:

There was a sweet shop at Durban and Camp Street. On visits to the shop, we could see sweets being made. The boiled sugar resembled a bundle of chewing gum and the owner of the shop could be seen stretching and making the mixture malleable by placing it on a wooden peg while stretching and pulling. The shop specialised in a sweet called “Neva done”. It was a candy more than a sweet.

There was no tradition of children receiving pocket money. Occasionally, family members would visit and give you a ‘freck’ or a ‘small piece’. We also earned ours through ’graft’. The arrival of soldiers from the United States during the WW2 provided us with extra opportunities for pocket money. It was the practice of churches to raise funds by printing cards which allowed donors to punch a hole on the card and donate money for each hole made. Small boys exploited this by getting the donors to part with their money. Many, including the soldiers, could not be bothered to punch a hole on the card. In any case, the card was often out of date.

We somehow managed to place a cent, instead of the penny given to us, in the collection plate at church. We did not set out deliberately to reduce the stipend of the minister but charity stays at home. We also collected bits and pieces of metal, empty bottles, the foil in cigarette packets which was made of aluminium – our contribution towards winning WW2 while at the same time earning pocket money. A newly opened ice cream bar, ‘Brown Betty’ in Hinck Street, was a hangout for soldiers.

Marc Matthews

Carinya Sharples

Ra Hendrix

Occasionally the sight of a Blimp on the horizon added to rumours of the presence of German submarines in the Demerara River and assumed some reality for many of us, students at St. Stephen’s School. Reports of the arrival of a U-Boat with soldiers distributing sweets to children soon brought out our parents and aunties to rescue us from these Germans who, it was said, were trying to poison us. A day or two absent from school soon resolved the rumour for what it was.

My father, Frank, who was the bread-winner of the family like many of his countrymen, found himself without a job. What saved him and the family was his decision to study and obtain a certificate as a Sanitary Inspector. This

qualification proved to be the winning factor which gave him the odds over other applicants for the job of a Prison Warder. Maybe it is for this reason that the family placed much emphasis on education.

My father, now a government employee, was able to obtain a mortgage and bought a half-finished house at the ‘QQ’ Bent Street, Worthmanville, or ‘Packoo Dam.’ This is the neighbourhood I spent most of my growing-up years. Bent Street during the nineteen thirties and early-forties consisted of householders similar to my parents: tradesmen, teachers and a few tenants living in rented accommodation.

Looking back on those early days of living in Bent Street, what were the sounds, the scene, the smells which through time has remained with me.

The most memorable was the Kiskadee bird chirping its early morning reminder that it was a new day. Sadly, on my visits as an adult they were very few around due to their habitat being taken over by houses. Even the carrion crow presence was scarce.

There were certain districts in the Georgetown, such as Kingston, Albouystown and Queenstown which were foreign and virtually unknown to many of us .

The most memorable was the Kiskadee bird chirping its early morning reminder that it was a new day. Sadly on my visits as an adult they were very few around due to their habitat being taken over by houses. Even the carrion crow presence was scarce. There were certain districts in the Georgetown, such as Kingston, Albouystown and Queenstown which were foreign and virtually unknown to many of us.

<

Huntley grand and great grandchildren

I attended Lodge Infant School under the headship of Mr Austin but it was the memory of Mr Paris or ‘Sah Par’, immaculately dressed in suits, a Panama hat and, I think, a walking stick. He was to us pupils a ‘Red Man’. From early in our contact with Sah Par, it was useful to gauge his mood for the day by the suit he wore.

Lodge School doubled as a church on Sundays and a school during the week. This meant that the grounds of the church/school was also the burial ground. Most of the graves or coffins were enclosed in a tomb, each of which had spiked railings. The graves must have been the resting place of well-to-do citizens including a Dutch planter or two.

However, we were not concerned with such historical details, nor indeed the likelihood of desecration of the graves of the dead, nor jumbies. Indeed it became our playground. The souls of spirits of the dead had little or no impact on us. In fact, we enjoyed husking the coconuts which grew among the graves, using the spikes of the tomb to remove the husks.

Although our parents were Methodists, as youngsters we attended the local Salvation Army Church situated at Halley and Bent Street under the leadership of the Moonsammys. I took part in my first and only nativity play.

This couple were the pioneers of the Salvation Army in the country. I recall them being poor and with very few personal possessions. Unfortunately, as we got older we attended the Methodist Church. The Salvation Army not only brought music to our lives but also provided the early start for many who learnt to play a musical instrument. One of the beneficiaries happened to be Keith Waithe, the renowned flautist, who is present here today.

Not very far from the Salvation Army were the Veerasammys. The family had a shop, horses and cows. The horses took part in the races at Durban Park, within walking distance from Bent Street. So, the street was a mixture of life in a town and country alongside each other. Lodge Village was indeed a village, with few houses, with opportunity for fishing and swimming in the backdam.

This may be a good point to share my experiences with members of the East Indian Community.

The Verasammy family was the exception to those with whom we had contact. The Verasammy, like that of Moonsammy, is indicative of the cross-section of Indians who were indentured. It was clear by their names that they did not come from Calcutta or Uttar Pradesh.

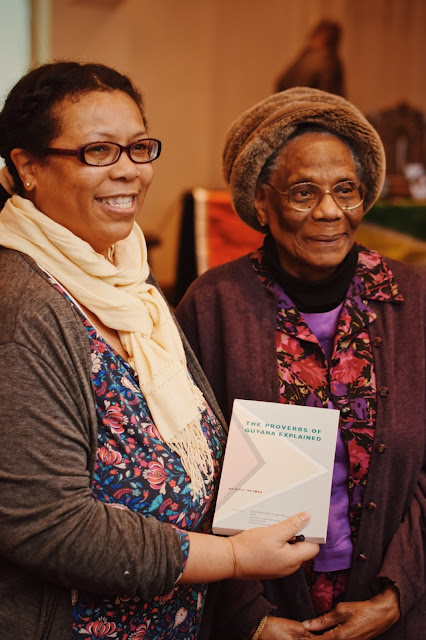

Joyce Trotman signing a copy of her book Guyanese Proverbs, published by Bogle L’Ouverture Publications.

One of the daily spectacles of the Bent Street years was the weekly trickle of Indian beggars who would leave their homes in Campbellville and the environs of Georgetown to beg for alms from house to house.

My mother like most of the neighbours always managed to find something to put into their bags or cups. Some rice, an eddoe, a plantain.

My father as a Prison Warder was responsible at times for supervising a gang to work in the Botanic Gardens or at Government House in Carmichael Street. My brother recalled that Governor Lethem’s wife once gave my father some of her letters to burn. If only he had had the foresight not to do so but to keep them?

It was my job to leave Smith Church School, go home and collect the carrier, a most convenient three-tier container which kept the food warm. The trip to Government House at midday was a challenge, amply rewarded however with sharing the prisoners diet of dhal and rice before returning to school at Smith Church. I have loved dhal ever since.

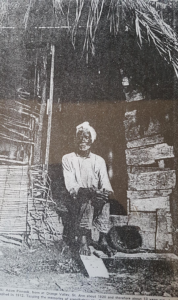

As a pupil of Smith Memorial School, we went to the public library, but never to the library itself. Instead we would go to the museum on the first floor and listen to talks given by Mr Williams, or ‘Soda Duff’ behind his back. He opened our senses to the animals, fauna and life in the interior of our country. At the entrance of the library was a caricature figure of an Amerindian or ‘Buck’ as they were generally called. While above, we paid homage to their way of life and culture.

The first time I saw a revolver was the one issued to my father after the prisoner named Coultruss escaped and was found at the back of the Botanical Gardens.

Every street, I imagine, has its source of notoriety. To break the monotony of respectability. Ours was ‘YY’ yard. A den of iniquity as the pastor or magistrate would say. Fights, quarrels, beatings was the order of the day.

One day its reputation, or rather notoriety, was more than deserved. One of the boys, on seeing his mum naked for the first time, ran out of the room and broadcast to the yard and the street that he saw a tarantula between his mother’s legs.

Much of our sex education came from the animal world of donkeys, cats and dogs all of which had no inhibitions. Many years later during the fifties in Howes Street where Jessica grew-up, the screams of a young girl alerted the neighbours. Her parents had rubbed a hot pepper in her vagina so as discourage her from engaging in sexual intercourse.

The upper half of Bent Street near the jail also had its moment when the entire street turned out to witness the consequences of a Bakoo escaped from its bottle and began throwing all the contents of the house through the window.

We, as expected, kept our distance from such un-christian goings-on. We kept company with our next door neighbours, the Osbornes. Mr. and Mrs. Osborne lived comfortably. He had a radio. He worked at the club catering for the relaxation in the evenings of the commissioned officers in the army and police and the white expatriates in Kingston.

Our relationship was however at a price. It was my job to make sure there was sufficient wallaba wood to fire their stove. Yes, they had an iron stove with facilities for baking.

My brother Rudolph and I would polish their furniture every year a fortnight before Christmas. Cabinet makers learnt the skill of applying polish using cotton-wool lightly applied to the surface. It’s an art and skill which brings out the layered surface of the grains in the wood. Lower down the social ladder, we would use varnish applied with a brush! We were in this category.

Writing about Christmas and polished furniture is a good time to reminisce about the seasonal festivity.

I do not recall ever seeing a Xmas tree or card. A couple of nights before Xmas families would made their way to Croal Street. There would be stalls selling balloons, six-shooter or single-shot guns, dolls, drums, sketch sheets and other articles associated with the festive season; peanuts, mittie and other refreshments would be on sale.

More often than not the toys would last a few days and we would have to fall back on the playthings made by ourselves. We made guns from wood, slingshots, spinning tops from orowo seeds and would re-use the cotton thread wooden section, attach a piece of rubber and obtain a crawling motion from it. We would get an old Ovaltine tin, put some sulphur from matches or caps from our six-shooters, spit in the tin, strike a match and keep our distance just before the cover of the tin would blast away. Terrorists of today cannot be compared with our ingenuity.

The highlight of Xmas was the way our mother would transform the house during the night. We would be put to bed on Xmas Eve and it was as though fairies or elves secretly visited the home during the night. When we awoke the next morning, the place was transformed. Xmas morning and the windows of each house in the neighbourhood would be thrown open to the smells of delicious foods.

No Father Xmas, no snow and no Xmas trees. New blinds, not curtains, furniture varnished, new lino on the floor, the smell of ginger beer, ham with clove, garlic pork and pepperpot. We could do no wrong! No licks on that day, as Mother Sally, Centipede or Santupee band, an Indian man walking on broken bottles, a walker on stilts that reached high enough to touch the windows in the gallery of our house.

On Xmas Day, we would be given a tray of goodies, a piece of cake, ginger beer, an ice apple, for each of the neighbours, particularly those with whom we may have had a quarrel. A day of reconciliation, peace and goodwill.

While we looked forward to Xmas, August holidays were fun in parts. Unfortunately, we did not have relatives who lived in the country with whom it was possible to spend some time.

Every time I remember old time story, water come a meh eye.”

During the rainy season, when play in the open yard was to be avoided, the Bottom House became our refuge where we could indulge in marble games such as jumming. Bicycles of our uncles or friends could be repaired of defective breaks, chains or punctured tyres. As children we did not spend much time indoors.

Four decades later, I learned that the Bottom House of my childhood became a favourite space for political and cultural gatherings by the Working People’s Alliance activists. From one refuge to another.

August could be a long month. The opportunity of getting into trouble not with my father or mother but with my big sister, Vera, the first born. She ran the house. Playing marble games was one thing but the habit of using the buttons on one’s trousers, meant our trousers would not be able to “stay up” if we lose the game. This really aggravated my sister. Several hours were spent unravelling the knots in the coconut fibre which filled the mattresses. The dust, none of us liked it. Worse of course was the practice of giving us a purgative to cleanse our system for the September school term. This consisted of nine days of senna leaves or pods and castor oil on the tenth. At the end of that week we were lucky to still have anything in us to flush out. The scrubbing of our outward skins with carbolic soap and that of our insides with laxatives left us drained. Our sisters used clothes-pins to straighten their noses and ‘Palmers Skin Success’ to lighten their skins.

Despite this undue attention to our abdominal areas, the times afflicted young and old alike with fevers, malaria, colds, chigger, worms, nara and TB. Fevers and particularly malaria were so rampant that it led to the government introducing a countrywide programme of spraying the likely habitat of mosquitos with DDT.

While most of the above ailments could be traced to the source in medical terms, the issue of NARA remained perplexing. Many boys including myself were incapacitated with pain in the lower region of their abdomen. Visits to the doctor proved fruitless and it was left to local treatment, mostly East Indian, to cure the ailment. Once well, we could explore the backyards of neighbours’ houses for fruits while keeping an eye out for marabuntas.

As small boys, we were able to avoid walking along the road to keep out of sight of our parents and walk along the alleyway at the back of the houses. We could walk from our house all along to Hardina Street. This has long ceased to be the case.

Indeed it is no exaggeration to state that not only have the alleyways but also the canals, which provided drainage regulating the water supply in and out, been totally destroyed.

Very, very, very sad.

My morning duties before leaving for school involved taking care of the fowls, making sure that the hens, which were about to lay, were securely kept in the pen so as to prevent them laying their eggs elsewhere. My mother would listen for them to “Cackle”, a sign that they had just relieved themselves of an egg.

The only way we knew whether the hen was ready to lay her egg was to place our middle finger in the rectum or bottom of the hen to feel the egg in her bowels. We also had a goat that needed to be taken to a near-by pasture for grazing.

By midday the goat would have to be given water to relieve its thirst due to the heat of the sun.

I attended Smith Church School in Hadfield Street. The school shares its name with the Rev. John Smith, minister of the Congregational Church, just opposite each other. The pastor arrived in the colony in 1817 and was warned by Governor Murray of Demerara that if he ever attempted to teach the slaves to read he would be expelled from the colony. Learning to read, even though the main source was that of the Bible, was regarded by the planters as subversive to their interests. We made the link quite early that education had a positive role to play in our struggle for freedom. Something the enslavers also understood.

In 1823 reports reached the colony, over-heard by Quamina, a house slave at Plantation Success on the East Coast of Demerara, that the governor had been sent instructions from England forbidding the flogging of women. The talk at the dinner table indicated that the planters intended to disobey the orders. It did not take long for the news to travel from the dinner table to those working in the field.

Quamina, a deacon of the church, is reported to have sought the advice of his pastor, Rev. Smith, as to the veracity of the report from England.

The insurrection lasted for two days but not before nearly three hundred slaves were killed. Not satisfied with such a massacre, the courts sentenced another forty five to death, whose bodies were put on public display to terrorise the living and as a deterrent.

Rev. John Smith was arrested and tried by court martial for ‘promoting rebellion, discontent and dissatisfaction’ and for failing to report the plans of the slaves. He was found guilty and sentenced to death.

When the news reached England there was outrage among the abolitionists who organised petitions demanding his release. However, Rev. Smith was not to live to receive news of his reprieve. He died in prison on the 8 February, 1824, and was buried in an unknown grave during ‘fore day morning’.

His name is commemorated as ‘Demerara Martyr’ – the first to be recognised as such. His death, and the viciousness of the retribution meted out to those who fought, helped provide that extra spark to the campaign for the abolition of slavery in England.Needless to say pupils at the Smith Church School were not taught any of this history.

‘When I remember ole time story, water come a meh eye’

My fondest memory of the church was the atmosphere at Easter time. It overflowed with palm leaves and sugar-cane, the bounty of the labour of the congregation and of nature, by the gifts of sapodillas, mangoes, oranges, ginnep, pineapples, sugar cane, golden apples, cherries, guavas, lovely plaited loves of bread and a lot more.

Eric Huntley with chirldren (Accabre and Chancey, daughter in law – Yvette) grandchildren (Hatty, Makeda and Senzeni) great grand (babe in arms).

Visits to Bourda market on Saturdays was an adventure. My first stop was a stall which allowed one to read magazines, mainly comics, for a penny. By juggling the money I was given, I was able to find a penny or two for a mauby and a cake. On the list would have been soup bones and fish-head. I cannot remember ever buying stewing meat. I was sent to Water Street, nearest Tiger Bay, to buy Broken Biscuits which was cheaper than the whole ones. Others were worse off, like buying two ounces of salt fish and asking for an onion to go with it.

The highlight of Sunday morning was an omelette in which water was added so as to ‘stretch’ the meal and make it do for the whole family. The only time the children were given an egg was on their birthday. To this day, I don’t understand what my mother did with all the eggs. Sunday Breakfast, not the first meal of the day but none the less known as ‘Breakfast’. Split peas soup of which the main ingredients was peas and soup bones, some of which would have small amounts of meat on them, these were served for the man of the house, the breadwinner! We, the children, got what I considered the best part, the bones with marrow.

After consuming the contents of the soup, dumplings, eddoes and so on, we all sat on the back steps, yes, we lived in a cottage with a front and back steps and spent as much time with bones as we did with the body of the soup. By the time we were finished with the bones, they were as white as the clouds. I do not think the dog or two waiting patiently in the yard for scraps made much of the remainder.

By three o’clock, just before we left for Sunday school, the mittie seller of Indian sweet meats would pass by and crown our Sunday breakfast with his delicious delicacies. I have always associated mittie as of Indian origin, however I recently learnt that it was traditional in Ghana.

We left Georgetown to live in New Amsterdam in 1943, leaving all my friends and starting all over again as a pupil at All Saints School.

“Every time I remember old time story, water come a meh eye.”

What exactly is meant by these words? What was it in the hearts and minds of our ancestors which provided the fuel for such sentiments?

One of the features of our rich oral tradition is that there is a void in the stories of enslavement passed on through the generations. That is the case for many of us who are looking for heart-rending memories of brutality. Is the reason for this void due to the tears that would be shed on remembrance? In its place, we have been bequeathed what A.J .Seymour described as a body of ‘beliefs, notions, prejudices, rituals, superstitions and traditions that are part of the national lore’

The stories of our antecedents were certainly missing. However, this void was filled with the way our parents lived their lives together with the words of wisdom which from time to time left their lips. Long after leaving home our ears ring with:

‘All play and no work mek Jack a dull boy.’

‘The lives of great men reached and kept were not attained by sudden flight but they, while their companions slept, were toiling upwards through the night’

‘Picknie ask ‘e mumma wah mek ‘e mouth so long, mama say boy your time will come.’

‘Every moully biscuit, gat e’ vung (smelly) cheese.’

‘Wha sweeten goat ga’ hurt ‘e belly.’

‘Black man a tief, he tief half a bit; bacra tef, he tief whole estate.’

Bequeathed to future generations, it has also left its mark in the realm of medicinal plants. Nearly a hundred have been listed which does not include those handed down by the Amerindians.

What has come down to us in Guyana is a rich heritage of proverbs and folktales. Sixty decades after the end of enslavement, proverbs and folktales became the oral manifestation of preserving our African heritage. This was not, as we might have expected, on account of our torturous journey but instead jewels of inspiration.

It is truly exceptional that, in 1902, half a century after abolition, we are indebted to the Rev. James Speirs who was able to collect and publish over a thousand proverbs.

We also owe a debt of gratitude to Joyce Trotman who was responsible for rescuing the publication from obscurity and later to Bogle-L’Ouverture Press for a new edition. In the anthology of ‘Caribbean Folktales & Legends’, the editor, Andrew Salkey, saw fit to include half of the contributors who were Guyanese. No wonder John La Rose, the publisher and poet, described Guyana as that remarkable “country of the mind”, paying tribute to the profound contribution Guyana has played in the creative sphere of our daily lives.

I Thank You!

Photos credit and courtesy Eddie Osei

February 2017

Shout Out

Next Guyana Speaks

Sunday 26th February