Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

Guyana Trip July 2017 II: Camp Street Prison Fire – a personal account

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 17 minutes

- Article

Share

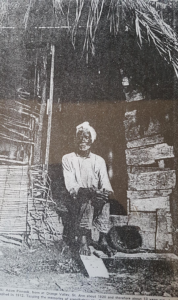

I arrived in Guyana one week after the Camp Street Fire that burnt down Guyana’s infamous top security prison. Located in the city centre, against better advice and calls for decades to relocate it, this was the most major of several calamities befalling the prison. Many before this calamity, and since, have suggested relocating it to the Linden Highway where there is sufficient land space to accommodate it. The original construction was ordered, I read somewhere by Queen Victoria 133 years ago. Her ghastly statue remains, as do many other symbols (physical and psychological) of colonialism, dominant outside the High Court. That says much. British Law and what else persists in the way Guyana is governed.

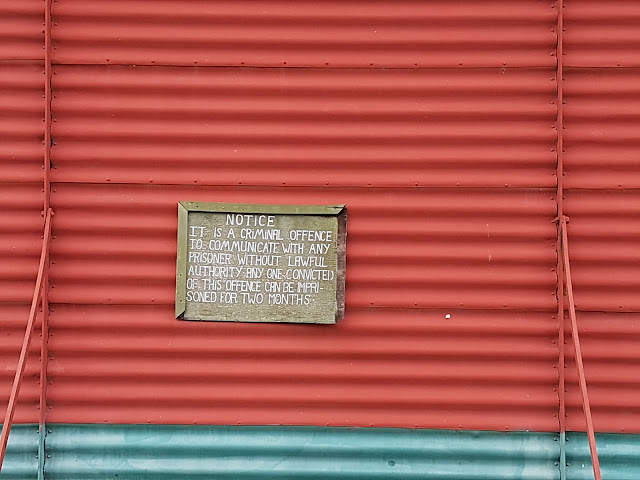

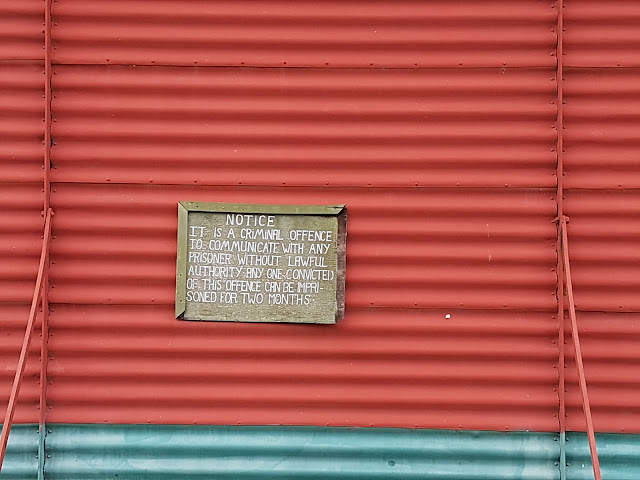

The reason, we’re told, for keeping Camp Street Prison so close and personal in the lives of local residents has something to do with proximity to the Supreme Court for those on remand to get there quickly. The fence is hardly high enough to prevent missiles of goodies and baddies to be lobbed over it. There is a sign on one side of the wall prohibiting contact/communication with prisoners. This is surely a parody that justifies the need to move it elsewhere.

By now citizens of the world ought to be aware public inquiries, following some state disaster are costly and often wasteful. Governments rush to order them after a major tragedy to appease its public that justice is being efficiently served. An inquiry was conducted after the 2016 fire at Camp Street in which 17 prisoners perished. Recommendations were made but not implemented because it would be too expensive to do so. A year later and another major fire that will once again start the chain of events; another costly inquiry, more recommendations, with the likelihood of there being no satisfactory outcomes.

Let me back up a bit

On 9th July my cousin sent me a WhatsApp message about the fire. Had I not seen it on Facebook? I had been to the river doing a ritual, so was on a good vibe (no social media) that day. When she shared pictures of the blaze, it became difficult to breathe. I was afraid for my brother who had been at the prison for the past three months. He was remanded there, charged with ‘possession of narcotics with intent to traffic.’ Weeks before in London I had bawled with the nation over the Grenfell Tower Inferno, for which ‘authorities’ have yet covered up the numbers that were consumed by it. We know the toll could never be 80, a figure they dragged out over weeks and have neatly squared for our consumption. I feared my brother might be a victim of the Camp Street fire and didn’t learn of his safety for a rough, sleepless 48 hours. I couldn’t tell our mother, she was already on a prayerful mission to get him released from there. We learnt that the authorities had decided to divvy the prisoners between Berbice, Timehri and Mazaruni. Eventually many were transported to Lusignan on the East Coast. I eventually learnt that my brother was among those.

Let me back up a bit further

My brother and I, as all siblings do, disagree on a number of things. He has been a Rasta since youth, smoking weed, as I did in my youth. He defended himself previously in the Courts in London and had never been incarcerated for possession with or without intent to do anything there. That changed when he returned to Guyana. A few years ago he was sentenced for three years for selling marijuana. It tore our mother up – in her twilight years having to deal with that stuff was too much. She is strong, however, praying through those trips to Mazaruni on the wily speed boats to visit him, and later to Berbice to where he was moved. My brother has had dealings with Guyanese police with regard to marijuana countless times. So when we received the call on this occasion that again he had been arrested to say I was angry, my mother frustrated would be understating our feelings. I can’t go on about how much and for how long before that anger turned from him to the stupid legal system that imprisons people for minor offences like possession or even selling Marijuana; when in a hot minute this will be made globally legal. My brother was refused bail at his first Court appearance. New court date served. Bail was refused again. Each time he went he appeared without a lawyer, since he is capable of speaking and defending himself, and ultimately since he believes by reason of his faith and culture that there is no legitimacy for locking him up for marijuana possession or trafficking. It’s not cocaine. It’s not large quantities. In this case, when we eventually got to speak, he said it was no more than 3 ounces.

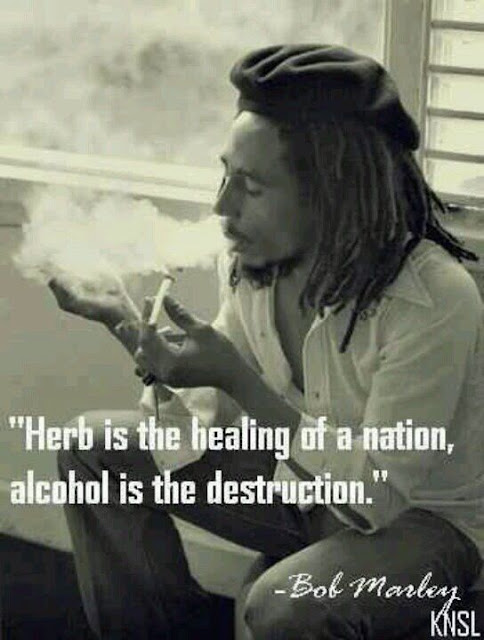

When I last saw my brother, in October 2016, he had been singing a tune I didn’t pay much attention to. He believed the government, spearheaded by David Granger especially, were going to ‘legalise’ marijuana. I’ve since learnt that ‘liberalising’ the law on marijuana was part of the coalition mantra, earning them relevant votes from young males and particularly from among the Rastafarian community. My brother is a Rastafarian who has naturally been championing the protracted global call for legalising marijuana, so it seems he ran away with the idea espoused by David Granger and the Coalition government that they would free up the herbs. The pre-election promise, it appears, is yet to be fulfilled because numbers of young (mainly) African men and Rastafarians are targeted with arrests for possession and smoking weed. These charges account for disproportionate numbers of prisoners at Camp Street. And on remand. A friend relayed that on winning the election in 2015, Bob Marley’s ‘One Love’ track was played for the Coalition’s victory celebration, he noted no less that Marley’s memorable tunes were compiled with a pen in one hand, a joint in the other.

When I arrived in Guyana I learnt that a Rastafarian Conference would be held at the University. I went. It was sparsely attended but there were some worthwhile presentations. I saw the near end of one that spoke about the relationship between reparations and repatriations – the latter needn’t be literal but should be contextualised as reclaiming history and decolonising the mind. I missed the one on ‘decriminalisation’ of marijuana as opposed to ‘legalising’ it. During Q&A I learnt though that this was based on the assertion that the Rastafarian community (he was referring particularly to Guyanese, but the Conference appeared international in scope), were not organised enough in terms of readiness for legalisation. Legalising the trade in marijuana would open up the investment potential to anyone. Those with resources, inside and outside of Guyana could easily purchase lands to accommodate the development of an industry that could see Rastafarians outwitted in their own back yard. Eric Phillips, director of African Cultural Development Association (ACDA) presented passionately about the same lack of organisation when he said that despite calls (he mentioned from the Government) to tell it what the community needed, no proposal had yet been made. This could, he was suggesting, include a proposal for acres of land on which to farm. This needn’t be as per individuals vying for small house lots or even farm plots but as a considerable collective. I had the cringing sense he was scolding the community like a school master might. He seemed frustrated, but I can’t speak to the intricacies of his apparent vexations nor the response (or lack thereof) by the Rastafari community.

I kept asking myself why after the fire and knowing that many of Camp Street’s prisoners were there on marijuana charges this community had not stampeded the government offices demanding immediate release, not on bail, but with charges dropped of those prisoners on remand for pitiful amounts of marijuana. I know it’s a legal issue, but really, what kind of ‘legal?’ Fair, just? I couldn’t understand the hush, either, and the lack of mobilisation and organisation by anyone actually in demanding something radical is progressed after this new fire, and especially after there were recommendations from the last one that were ignored. The business as usual thing bugged me. I am not amused by the chorus ‘this is Guyana’ that excuses all kinds of lawlessness and stupidness.

In London (even bearing in mind cultural, social and economic differences) Grenfell residents and supporters stormed the affluent Kensington and Chelsea Council premises demanding answers since the Council was culpable and had to be called to account. They had been warned about a possible fire by a residents group but ignored them. Likewise, the Commissioners of the previous inquiry after the 2016 Camp Street fire had, according to Guyana Chronicle “noted that repeat offenders have increased by over 100 per cent, “indicating not only a waste of taxpayer dollars but also the need for a more comprehensive and structured partnership within the wider justice system.” Clearly, something had gone and had been going terribly wrong for some time. Why wasn’t the moment seized to challenge the legal system that disproportionally criminalises African males, especially where the charges are related to marijuana and by inference therefore for choosing the Rastafarian way of life? The silence continues.

They’re rebuilding Camp Street?

I prayed before travelling to Guyana that I wouldn’t find my brother in prison. Whilst at times we disagree on things, I’d challenge anyone who thinks they can condemn him for his beliefs and even his actions. My issues with him and what I consider a kind of obsession with marijuana (despite its cultural/social/religious significance and health benefits) has as much to do with my spiritual growth as that of my brother’s. When a mother, an elder is heartbroken because her son, not a child, a grown man with children of his own faces the prospect of imprisonment yet again for the same offence one has to ask whether it is really worth it. It seems so to him, whether I/we like it or not. In any case, I had hoped he’d be released, even if this meant he’d be given community service. He had a court date on 20th June. The magistrate didn’t give him any hearing but instead cancelled the session and gave him another date, thereby putting him back on remand, with the near possibility of him being a victim of the fire that took place on 9th July.

Having arrived in Guyana, a week before the Diaspora Engagement Conference, and one after the fire, I visited the site. The fire had indeed flattened the wooden part of the prison. Only the two concrete buildings remain. Work men and machines were labouring on the sandy site, smoothening it with no trace of debris (perhaps bodies – my mind overran!) visible. My cousin was with me, “what they doing to this place,” he asked one of the workers. “Rebuilding it,” the workman said, sadly, his eyes looked deep into ours as though he wanted the weight of those words to penetrate our souls.

The Police mess across the road was also burnt, but being concrete is reparable. A nearby house had caught fire; cables looked ominous and now useless as they too were caught by the blaze. It was a Sunday, naturally it was quiet. But this quiet was not natural. Small children watched us as we walked the perimeter of the prison, their eyes and those of the odd parents/older family members we saw looked sad. Or was it shame I was seeing? For when at last the locals might have felt freed from that blight in their neighbourhood they were instead faced with the horror that the site would be rebuilt to once more contain the most violent members of the wider Guyanese society. A smaller fire had taken 17 lives a year previously, it was, therefore, difficult to accept the official report that all 1018 prisoners survived the blaze.

What follows is based on a conversation I had with my brother after I paid a supposedly ‘reduced’ bail (when there had been no issuance of any in the first place) that has given him a hint of freedom.

3 ounces of Marijuana – bail denied!

The story goes that my brother’s neighbour was robbed. In their routine investigation to find out if locals knew anything about it, they came to my brother’s home, discovered his bagged out weed and arrested him. Bail, as he had expected and messaged me in London to hopefully secure somehow through my at the time vexed face since we didn’t know where else we’d find it, was denied. He had to go to court.

Prior to the fire, my brother had been trying to secure bail, each time the magistrate said ‘No bail.’ The fire provided the exigency for the court authorities to award reduced bail for ‘minor infringements’ and since many of those in Camp Street were there for petty crimes, the Coalition government’s pre-election promise to liberalise the law on marijuana became an inconvenient imperative.

The fire

‘Smallie,’ or Mark Royden Williams, dubbed the ‘mastermind’ of the prison break is a Rasta like my brother. He didn’t (at least at this time) eat salt. And as my brother had been working in the kitchen, he was put in charge of cooking meals for all those prisoners who didn’t eat meat and ate only Ital. My brother is an excellent cook. He said that ‘Smallie’ seemed to be ‘running things’ in the prison, for example, making demands on the guards and officials for whatever he wanted. This was mainly around his meals. If they scrimped on seasonings, so that meals were made without tomatoes and adequate seasoning, he refused to eat it. The officials scurried to find requisite items and a new pot of meal was prepared.

According to my brother, the first attempt to escape by the means of setting alight the prison was last year. That plan was foiled. Allegedly a known official was overheard saying ‘let them’ (the prisoners) burn!’ Obviously, there’s no way of verifying this. The 17 who did burn were in this instance being avenged, at the same time as there being a renewed plot to escape. My brother said some of the prisoners who had escaped last year’s fire were traumatised, some coiling up in foetal postures when relaying the story to him, turning their backs from the terror of memory.

The fire was possible because the guards were docile and sleepy, particularly on a Sunday afternoon, either from overeating, drunkenness or weed smoking. Once ‘Smallie’ and the main actors in the break out had overcome the guards, by means of struggle, including chopping an important figure (whose title now escapes me) as they went along, a sight my brother said he had to turn his face from seeing, they released other condemned prisoners. That ‘figure’ (the ‘OC’ I believe, but don’t know what it stands for) was detested by the prisoners as he was cruel. The ‘plotters’ made sure the prisoners were safe before setting alight the prison, in strategic locations. Some of the male prison guards ran from the prison leaving their female counterparts to face not only the fire but the prisoners. As the chaos ensued, my brother and other prisoners made it to the gate, awaiting transport across to the mess, but this too was soon set ablaze; from that frightful scene too the prisoners were later transported to Lusignan. ‘Smallie’ and accomplices were long gone. Given that they were high security offenders, who are still on the loose, I am astounded by the silence. But I don’t live in Guyana and some things I naturally won’t be able to get my head around. In any case, my brother surmises that there is some kind of vendetta yet to be fully played out between the escaped condemned prisoners and the Chief of Prisons, Gladwin Samuels.

I was told, on a separate occasion by an ex-policeman, who had left the job because of the corruption it carried being part of that system, that the other ex-policeman (Uree Varswyck/e?) who had escaped with Smallie, had also become hardened by his experiences on the job. He, being well trained from overseas and having ambitions beyond his present rank was tasked with training (with drills etc) other officers and sometimes senior ones. There arose acrimony between him and these senior officials who couldn’t handle his (as a junior with more experience) ‘orders’ and would challenge him and make life hell for him. He decided to quit. But this didn’t stop the bullying and eventually charges, the ex-policeman said were trumped up led to his arrest and imprisonment. Again, there’s no way to say which of this is true and which myth. But Varswyck too raged and holds a vendetta – and is now on the loose, with his skills as a trained killer intact.

Cramped and stink! My brother reckons the numbers detained in this hell hole superseded the figure of 1018, pushing to more like 1200 or more. When he had arrived at the prison, he was expected to sleep 3 men to one small bed. He bought some material, as did others and made himself a hammock, sleeping above other prisoners like big bats.

When he got the job in the kitchen he said it was disgusting, roach infested (though I can hear the shrewps that this is nothing when these vermin are sometimes seen in homes and hotels!) But it’s the image of this blackened, stink mop with which he was expected to clean the kitchen that stays with me from our discussion after his bail release. He bound his belly and began scrubbing the mop with his bare hands. Now my brother is super scornful so I can’t even imagine him doing this, and don’t think I could have done it myself. But he said, when other kitchen hands saw him, a Rasta do this, they too followed suit and began to take active/conscientious part in trying to clean the kitchen.

Prison officials were deliberately retaining government supplies meant for prisoners, whether this was seasonings for the food or the quantity of peas and rice supplies.

There was a business racket in the prison, with profits of 300-500% compared to outside for items like the many mobile phones being sold there. These profits and trade are shared between prisoners and officers. The usual sum for any small payment (bribe or goods) might start at $5000. A credit system operates in the prison and is the means by which items are purchased. For example, a family member on the outside tops up the prisoner’s phone with credit which they can use to trade for necessary items, but one might suppose this is current in other countries around the world.

The bail release

On the Monday morning after I arrived in Guyana, I called Lusignan prison, thanks to contacts friends in the UK had in the police who had given them an officer’s details. The senior officer to whom I spoke sounded understandably stressed and asked me to call back a few hours later. When I did he advised that my brother was due for bail reduction and if we/he was ‘desirous’ to pay this he would find out how much. I found out the following morning it was to be $65,000. He instructed me how to make payment to secure my brother’s release.

I went to Brickdam at Prison Headquarters and collected the bail release form. I then had to take it to the magistrate court. As I didn’t know exactly where it was, an elder woman and daughter who were headed there walked with me to show me. The daughter said her son was also at Lusignan. He was taken to Camp Street following his arrest a few weeks back for alleged armed robbery. They said it was a trumped up charge by a police officer who was having an affair with her son’s child mother. The police officer had wanted the son out of the way so he and the child mother could be together, so he contrived this armed robbery which supposedly took place 2 years previously. She also related that her neighbour had once been arrested and served 3 years for having a small marijuana plant growing outside his yard.

The miserable official faces at the magistrates’ court looked like zombies propping up a tardy system that was oiling itself from the substance of their human energy. Behind their bars and uniforms, they seemed scornful of those on the other side. The young female police (there were a lot of young police offers I noticed and many African – this as compared with the numbers of young East Indians behind counters at the banks) who searched my bag as I entered the court yard did so with the life and conviction of a limp bird. She too, it seemed to me was doing some kind of time, food and home longed for instead of those hours in the heat and contrivance of a justice system.

As my brother’s case began in Linden, they couldn’t find his file or ‘Case Jacket.’ As there is no computer system, one of the clerks looked exhausted as she contemplated how long it would take to locate it. Eventually, they realised it was over the river, I would have to return in the afternoon as someone had to manually bring it across. I returned as instructed but was told the magistrate who would have to sign the bail release form had left for home – this was at 2pm. I returned the following morning, at 9.30am as the helpful clerk had advised, where upon she said she would ensure it was signed when I arrived. It wasn’t. I waited. One hour. I waited. And noticed that a number of people had been moving in and out and I was still waiting. At one time, by myself in this miserable antiquated place. I got vexed. What was taking so long? Like clock work in Guyana only when we perform like we really mad and gon tear de place down can we sometimes see movement. I said to the clerk I wasn’t blaming her. I had things to do. I have been patient. Where is the magistrate – and this was a genuine question, I wanted to see the face of authority that would be responsible for signing this document and perhaps challenge them as to why he wasn’t issued bail previously. I told them the magistrate needs to sign the form then as I’d come a long way to deal with the matter. It was returned within 10 minutes. I rather regretted not getting that chance encounter with the magistrate.

I had to find a policeman for the next process. I located one who would go to Lusignan and bring my brother to town. This young man also looked pained as though the weight of the work disturbed his soul. And indeed, he would relay to my brother that since joining the force, he had once been arrested (I can’t remember for what), but the ‘case’ was thrown out and he was restored to his job. But now with the pain of what it means to be part of that system enshrined on his brow. My brother had been given a new court date. It was on the day I was presenting at the conference so I couldn’t go. He showed up. The magistrate gave him another court date. It is a livelihood that comes with its risks. And though pride or something else might make him appear as though he’s weathering this new storm in his life pretty well, I think it’s taking a mental toll on my brother. I know it is on my mum and if I too could crush my pride, I’d say me too.

It’s beyond the purpose and limit of this article to record how many conversations I had with random people about police stopping and arresting young African males mainly for petty marijuana ‘offences.’ Guyana, I know is not the only country disproportionately imprisoning African males. Time also doesn’t allow me to consider the racketeering in the prisons, the sense that imprisonment doesn’t seem to be about rehabilitation or essentially justice but something else I can’t figure and why despite so many complaints about how the police themselves show scant disrespect for the law, taking bribes that prop up their salaries are they allowed to continue this racket with impunity. I hear the chorus, it’s a familiar phenomenon, state instruments protected/protecting itself and forgetting the public service fact of being sworn into the roles.

Conditions at Lusignan

They were put in a field, all types of offenders bound together. In the Camp Street chaos, according to my brother, most of the prisoners who left there had weapons on them because they had not been searched in the transfer. Fights between prisoners and even murder are part of the prison system. My brother says one murder took place when they moved to Lusignan. The officials originally hadn’t been giving the prisoners food – though they were being brought supplies. This was made expedient by the social media images of prisoners slaughtering a cow (I think some other animal too). When he was able, my brother called my cousin and told her about the slaughtering of the animals. He said when they start killing the animals (he being Rasta wouldn’t have been involved in this) one of the cows came up to him, with sad eyes as though saying ‘ow, ow, tell dem na kill meh, na kill meh!”

They didn’t have coverings to prevent exposure to sun and rain. Eventually, some kind of make shift thing was erected. And of course being in a field it was not long before we learnt that 13 prisoners had escaped from Lusignan. This was the day the Diaspora conference began when I watched President Granger make for the exit to deal with the situation. 7 of the prisoners were caught but the first ‘original’ escapees, including ‘Smallie’ and his fellow, condemned prisoners and now these from the field in Lusignan on the East coast, casting new shadows and textures of silence on the city as people continue the daily grind of surviving.

Shout Out