Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

The Spirit of James Baldwin

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 11 minutes

- Article

Share

‘The unexamined life is not worth living: and I know that self-delusion in no matter what small or lofty cause is a price no writer can afford. His subject is himself and the world and it requires every ounce of stamina he can summon to look on himself and the world as they are.’

‘The unexamined life is not worth living: and I know that self-delusion in no matter what small or lofty cause is a price no writer can afford. His subject is himself and the world and it requires every ounce of stamina he can summon to look on himself and the world as they are.’James Baldwin – Nobody Knows My Name.

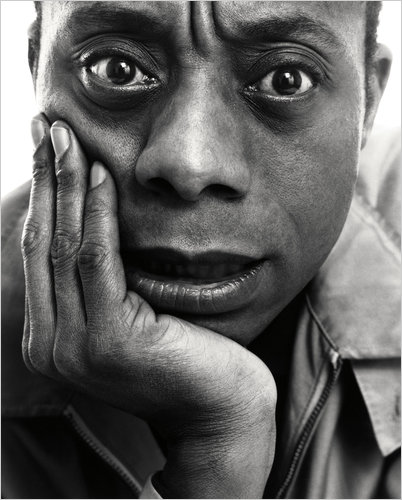

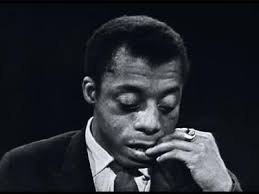

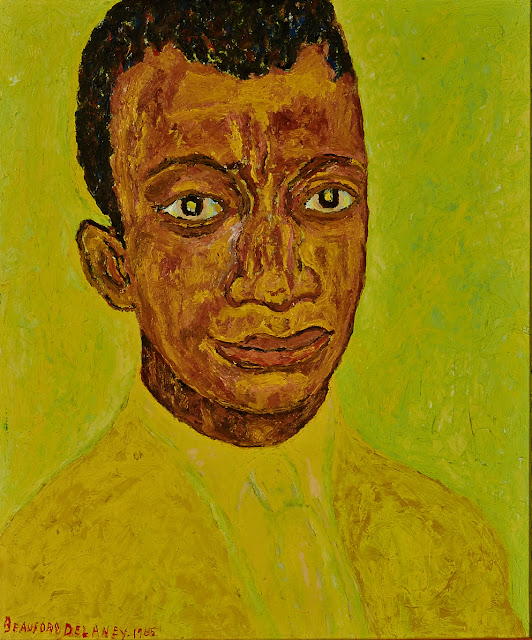

James Arthur Baldwin whose literary and prophetic brilliance has been catalysed most recently by the release of Raoul Peck’s I am not your Negro, is a man not so much seen or heard, but felt. This feeling, I see as the presence of a potent energy of spirit. The more I feel him, the more reminded I am of Esu, one of the Orisa of the Yoruba spiritual system of Ifa. This Shout is an attempt to share my thoughts about why I feel him in this way and why his presence (spirit/energy) has chosen now to re-emerge.

Who is Esu?

Descriptions, depictions and concepts about Esu are so abundant as to be overwhelming in a simple search to know who this important Orisa is. It’s accepted, however, that he is a messenger – of Oludumare (the Yoruba supreme being/creative life giving force, usually referred to as ‘God’). To whom does he bear messages? to Oludumare and us – human beings, standing therefore as a bridge between us and the creative force (God). It is accepted too that before making offerings to other Orisa we do so to Esu first, since he (and ‘he’ is often gendered this way) is that bridge. Varied perceptions about him proliferate because there is a slipperiness inherent in his essential qualities. He is both jovial – appearing fun-loving and full of wrath. His wrath has been conceived as ‘evil’ by European (white/Western) observers. They have associated his complex force with tricksterism, and ultimately he has been likened to the ‘devil.’

The dynamic and humanistic Ifa system holds no such ideas about ‘evil’ versus ‘good’ and ‘devil’ versus ‘God.’ There are simply routes, paths, progressive and digressive journeyings towards the advanced self – we might understand readily as fulfilment of our ‘destiny.’ When individuals begin to arise in consciousness they intuitively seek a better exploration of their destiny, and use all forces and phenomena available and ever present in the universe, seen and unseen, toward that end.

Thus the energy of Esu opens the way (think of it as preparation for spiritual awakenings, expanded consciousness); he is giving (bearing our messages to Oludumare). But he also forestalls, berates, and exacts punishments, manifesting in physical losses of material possession and psychic numbness whereby one feels stuck or unable to make sense of what is taking place in our lives/world. I’ll call this element a retreat of consciousness which might render an individual lessons in the truth of their actions and decisions that are wanton digressions from their destiny. This retreat can be as dramatic as yielding remembered trauma and depression in order to enable the individual to realign with their path. Or it can take the form of epiphany enabling the individual to more joyfully regard the unwitting challenges thrust upon them by Esu’s perfecting methods. Esu’s energy is therefore much more empowering than the simplistic binary of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ since it represents the complexities inherent in the sum of all human experiences.

Where the Esu force meets Baldwin

Baldwin saw himself as a ‘witness,’ which we can easily link to Esu’s messenger profile. His role as witness means that he could not isolate himself into any one narrative or construction of being human. Our obsession with single narratives, which is altogether limiting with the incumbent desire to categorise and box in ourselves make us squander a quality I think vital in understanding a presence (being) like Baldwin in our world. I call this quality our spiritual intelligence. It operates when one is able to look at someone and see beyond their physical appearance. When we’re able to acknowledge the spirit of an individual, we’re sharpening our spiritual intelligence whilst simultaneously aligning with the life giving force through which we are ourselves creative; we are advanced in consciousness, aiming towards our divinity.

It should not therefore surprise us when Baldwin’s biographer, David Leeming, writes that: ‘It was the calling to bear witness to the truth that dominated Baldwin’s being, and in this role he could be harsh, uncompromising and even brutally cruel,’ (1994:xii).

The truth, if told passionately is sometimes uncompromising and brutal depending on the receptivity of the heart or conscience to which it is directed. Baldwin’s target was the American nation whose guilty conscience would naturally consider him ‘cruel.’ I know Leeming was also referring to personal examples (of Baldwin’s ‘brutal cruelty’), but my aim is to posit a wider feeling of Baldwin. The central question posed to the American people, which Raoul Peck so masterfully determines at the end of the documentary I am not your Negro, is to ask why they (white Americans) needed to invent the ‘nigger?’ This question ought to be forever etched on the psyche of Europeans who sought to conquer the souls of Africans since the economic wanderlust imperative had to be accommodated by a much more pernicious and lasting subtext of their conquest. The question is not asked because Africans (in America and other parts of the diaspora) want to ring-fence ourselves in the perpetuity of victimhood or trauma but precisely to re-imagine our strategies to oppose the newest forms of oppression/domination we currently face.

The sexuality fixation

But instead of trying to deal with this question there is an obsession with Baldwin the man – and particularly his sexuality. At the screening of the film at Phoenix cinema a couple weeks ago where I joined Tony Warner to do the Q&A, this was the first question from a member (a European American/white professor) in the audience: ‘why was there an absence of his sexuality in the film?’ Some years ago the first time Tony invited me to do a Q&A on Baldwin at the British Film Institute (BFI), the first question equally was centred around Baldwin’s sexuality, which was not the focus of either documentary.

Often the fixation about his sexuality makes no mention of an adolescent ‘violation’ (at about age 14) when he was fondled by an elder man, which both aroused and terrified the young Baldwin. But his ‘witnessing’ is total; he was aware, of course, that adolescence presupposes evocative and evolutionary experiences that individuals choose to take with them through their life journeys or leave behind. Sometimes those experiences haunt us like shadows dancing at every turn of our lives; sometimes they liberate us from limited perspectives about what it means to be human. I would agree with David Leeming that Baldwin was ‘ambivalent’ about his sexuality (1994:xiii). For me this can be linked to his self-styling role as ‘witness’ but this ‘ambivalent’ aspect also aligns with his spirit as Esu.

Cursory readings about Esu reveal things like his love of sex, alcohol, fun, cigarettes and cigars, dancing etc (see for example Neimark 1993:72). He is not attempting to please, appease nor deliberately disparage by being this or that thing. He is a balancer of forces, if you will; redeeming polar extremes when necessary to set us back on track. Thus Baldwin’s force is to be a harbinger of rectification using any means possible – just as Esu would, even if those means are painful or pranks that force us to sit up, listen and make aright our transgressions.

The prophet and the hypocritics

It’s certain, as Douglas Field considers, that Baldwin’s ‘reputation has suffered from his refusal to adhere to a single ideology and his continued resistance to and suspicion of labels and categories,’ (2009:4). His critics, African and European (‘black’/’white’) wanted him to choose a position – identify himself as homosexual or heterosexual, be an essayist or novelist, live in USA or Europe, be a spokesperson for civil rights or a celebrity of white America’s illusions about ‘the negro,’ be a negro/black writer or a writer and so on. Writers, if we take this label alone, when committed to the truth of their art, would naturally shun such limiting fixtures. But no ‘prophet,’ as David Leeming has called him, would claim to be this or that thing given that the pendulum of human transgressions is ever in flux. Spirit is thrifty- adapting to myriad movements at the same time. Spirit is timeless also and mutable – in short, ‘slippery.’ According to Leeming:

Baldwin was a prophet not so much in the tradition of foreseeing events – although The Fire Next Time bears witness to the fact that he sometimes did precisely that – as in the tradition of the Old Testament…he understood (like prophets in the bible – Ezekiel, Isaiah, Jeremiah…) that as a witness he must stand alone in anger against a nation that seemed intent on not ‘keeping the faith,’ (1994:xiii).

The nature of this faith is simple: that every human being deserves the right to exist without fear of deliberate and systematic attempts to deny them every possible chance of survival. ‘I am not a nigger’ his spirit boldly declares on the screen, ‘I am a man.’ And that persistent struggle to be occupied his literary explorations throughout his lifetime, and is especially signalled in titles like Nobody knows My Name, No Name in the Street and ‘Stranger in the Village’ (Field, 2009:9). He feared death, as most of us do. But death brought about through nature’s course is one thing. When it is callously and continuously brought about by a strain of human deficiency and degeneracy hallmarked by white supremacists the pummelling of writer activists like Baldwin must be given the kind of attention Peck’s documentary has resurrected. The documentary emphasises a causal relationship between persistent racism and white supremacy, through its collaging of footages from the 1960s’ Civil Rights Movement and the present Black Lives matter Movement. But Baldwin’s spirit does not speak passionately only to white supremacists but to those liberals who are so charmed by their complacency of privilege they are unable to see how their silence on matters of unprecedented racist killings by Europeans against Africans makes them complicit in the degenerate actions of their forefathers and contemporary brothers.

I was informed by a friend (a writer, therefore naturally a ‘conversation thief’) that during the screening when we did the Q&A at Phoenix cinema that she had to endure running commentary by a couple of white women behind her chiming things like ‘it’s so biased, not all white people are like that.’ During the Q&A, in response to a question I said that there were a number of Africans disproportionately incarcerated or have mental health issues. One of the white (European) women seated behind my friend muttered to her friend ‘I think you’ll find they’re asylum seekers.’ I wondered why they were there if they weren’t prepared to allow the brainstem to properly perform its function of relaying information that would enable them to ‘keep the faith.’ However, a privileged psyche would find it impossible to excoriate its conscience and this embeds a fundamental contradiction of liberalism.

His critics wanted some barometer against which to measure Baldwin. For a time they compared him with other ‘negro writers’ like Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright, whose works have been given more canonical coverage than Baldwin’s within the academies (especially in the USA). But there has been a shift and realisation that it wasn’t Baldwin’s refusal to be pigeon holed that caused critics to overlook his literary worth, it was their misty shades that made him appear fuzzy, ungraspable and at times unpredictable.

Baldwin as Baba

The father symbol revolves in a lot of Baldwin’s work. His first book Go Tell it on the Mountain, about a boy preacher who challenges his authoritarian preacher father is obviously autobiographical. He didn’t know his biological father; knew only Reverend David Baldwin, the man his mother Emma Berdis Jones married when James was about three and with whom he had many battles. He contemplated these battles with his father (as he saw him and not so much as a stepfather), throughout his lifetime, one of these is powerfully rendered in the essay ‘notes of a native son.’ He had imagined he hated his father but later recognised that his father’s weaknesses, parading as authority and power, lay in the pervading psychology of racism that made it impossible for him to love himself and therefore to fully transmit that love to his children. His father’s psychic debilitation (he would die in a mental institution of tuberculosis) was rooted in the brutal experiences of trying to survive in a world white people declared was theirs. His father was frigid around white people, for they symbolised power over him. Baldwin resented observing how his father acted around white people. He hooked himself onto their model civilising order – Christianity – but could not transcend his circumstances on earth through its doctrines. For this doctrine taught him that salvation could come only through death, in the milk and honey land of heaven concocted for Africans to accept their earthly servitude while Europeans enjoyed the double experience of gorging on the nectar both on earth and heaven.

Esu is a ‘father’ symbol (baba). Baldwin didn’t have children of his own, but carried the essence and desire of a father as part of the witness/messenger persona. This was not least because he was the eldest of nine children whom he assisted his mother in raising, but in his role as witness he considered himself somewhat fatherly because of his single-minded mission to ‘save others through the word,’ (Leeming, 1994:4).

Finally, in a mindboggling moment when ‘keeping the faith’ of advancing humanity is up close and contentious in our lives, the spirit of Baldwin is timely. We might add to the question Peck’s documentary poses – why do American imperialists (not the populace) need to invent wars? To push us from our comfort zones, we might also ask how is it possible for a country, self-declared as the world’s avenging angel can arbitrarily bomb other nations without any provocation; an act thought to be a model of USA presidential standard (Obama’s version was Libya, let’s be clear) which legitimises, especially in Trump’s case, this presidency? The father conscience (Baba Esu) would err towards human progressiveness not backwardness, degeneracy and destruction. It would berate and chastise us into seeing sense, that our collective destiny is to advance our humanity not compete with one other, especially with ever increasing methods of destruction.

This need and resurrection of Baldwin comes now to remind us, as we mull over warnings about nuclear war with supposedly civilized world powers (USA, UK, Russia, China, North Korea and Iran) of the ‘moral bankruptcy’ of the nation that chimes the tune of war most vociferously, the USA. It was this nation that he loved and by which he demanded to be acknowledged as a man. So if Baldwin can be likened to the ever chastising Baba Esu, we must accept that intermingled with his ‘brutal cruelty’,’ and uncompromising truth and honesty was his stance that revival or return to the ‘faith’ lay in humanity’s ability to take seriously the power of love forever swinging on the pendulum of human transgressions. The intuitive feeling I have for Baldwin as Baba Esu penetrated that much deeper when I learnt that a Yoruba death drum opened the celebration at his funeral, attended by 5000 people who might not have known his name but now at last could feel the rhythm and power of his words.

A new The Amazing James Baldwin 6 weeks Course, led by Tony Warner, Michelle Asantewa and Donna Mckoy starts February 25th 2019. Book to attend now.

Works cited:

Douglas Field, ed. A Historical Guide to James Baldwin: Oxford University Press, New York: 2009

David Leeming. James Baldwin – A biography: Michael Joseph Ltd: Penguin Group, London: 1994

Philip John Neimark. The Way of the Orisa: Empowering Your Life Through The Ancient African Religion of Ifa: HarperSanFrancisco, New York:1993

Randall Kenan. ‘James Baldwin, 1924 – 1987 – a brief biography’ in A Historical Guide to James Baldwin. Douglas Field, ed. Oxford University Press, New York: 2009