Disclaimer: Use of Copyrighted Images

The images used on this

blog and in our newsletters are sourced for educational purposes only.

These images are the property of their respective copyright holders and

are used under the principle of *fair use* to support commentary,

analysis, and discussion. We make no claim of ownership over any

copyrighted images and have taken all reasonable steps to attribute them

appropriately.

If you are the copyright owner of any image

featured here and believe it is being used improperly, please contact us

directly. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights

and will take prompt action to resolve any concerns.

This content

is not intended for commercial use, and any reproduction or

distribution of the images without proper authorization may violate

copyright laws.

Walter Rodney reflections on The Groundings @ 50

-

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

By

Dr Michelle Yaa Asantewa

- 8 minutes

- Article

Share

On 15 October 1968, Jamaican Prime Minister Hugh Shearer, declared Walter Rodney persona non grata. Banning him from returning to…

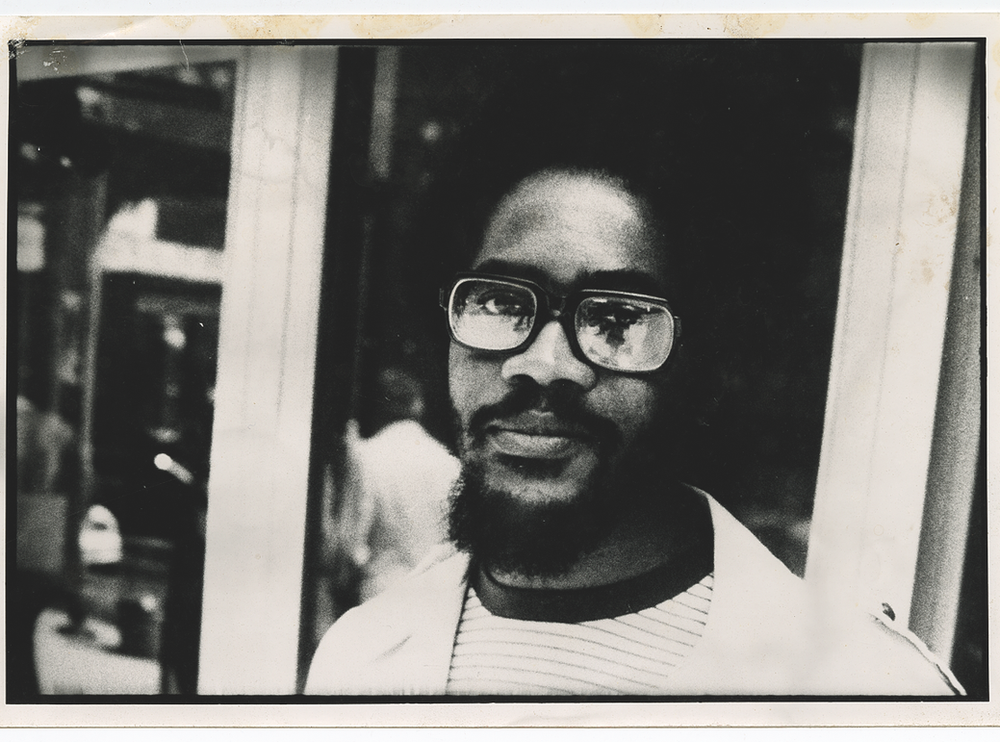

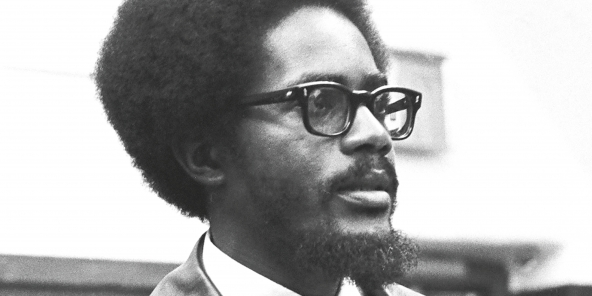

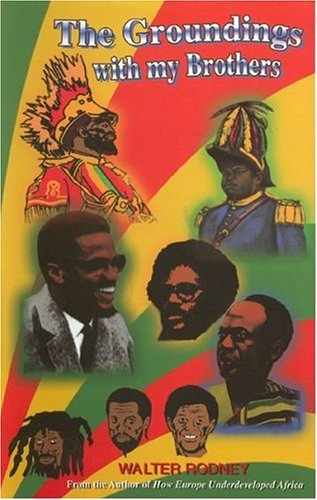

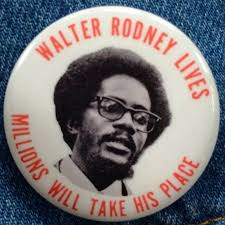

On 15 October 1968, Jamaican Prime Minister Hugh Shearer, declared Walter Rodney persona non grata. Banning him from returning to Jamaica, where he taught at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus led to protests by students and the working class peoples of West Kingston. The riots that followed – which started on 16th October – exactly a year to the day I was born – is known as the “Rodney Riots.” The banning occasioned the development of Bogle L'Ouverture Publications (BLP) co-founded by Eric and Jessica Huntley and others. Walter Rodney provided the lectures he was giving to the mass, local Jamaicans, particularly Rastafarians, which formed the basis of BLP’s first publication The Groundings with My Brothers, published in early 1969.

The Groundings provided Rodney a means to deliver a message, rather than a defence, to the establishment outlining the real catalyst for the riots that followed the banning. He argued that the main issues were impoverishment – spiritually, socially, culturally and economically that the masses were experiencing under a government that was no more than administrators of their former colonisers. “Former” is presumptuous as those colonising powers prevail in Jamaica and other underdeveloped countries we could name – but in Jamaica’s case this is symbolised by the fact that the Queen of England remains its Head of State. The administrators didn't want the masses, ordinary people politicised, and made conscious. Walter Rodney on other hand knew that cultural and political awareness was the principle means of their power, which would give them confidence. Thus in The Groundings he writes:

“What we need is confidence in ourselves, so that as Blacks, as Africans we can be conscious, united, independent and creative. A knowledge of African achievements in art, education, religion, politics, agriculture and the mining metals can help us gain the necessary confidence which has been removed by slavery and colonialism” (1969:48).

So when we find ourselves utterly frustrated and feeling demoralised by the scarcity of everything in our home countries (those in Africa included) we must understand that those who were “selected” by Western imperialists to govern us after the sham independence they “gave” us were in collusion to keep us in perpetual state of “underdevelopment.” That very process would form the second book of Rodney’s published by Bogle L’Ouverture namely How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972). Given our historical achievements, this persistent 'lack' we so frequently bemoan need to be put into context to acknowledge how it came into being and how it is maintained. Continuing with the importance of African history and culture to our development Rodney argues that “there is no evidence to show that racial discrimination was part of [ancient Egyptian] culture. Yet as part of the white men's way of seeing things, the red and black populations of Egypt would have been seen as 'coloured' and or 'negro'. Christ was a member of the Essene group of Jews from Egypt. Were he alive today he would suffer from racial discrimination,” (p.52). Ironically 'Christians' have a real issue with Egypt let alone acknowledging Christ as black – as the Rastas Rodney mingled with believed. So there would have been levels to this discrimination, after all it was Black men that banned Rodney – but though Black – they were ‘white-hearted', as he claimed.

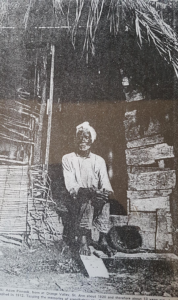

The point Rodney is making is that Africans need to be aware of the fullness of our history, especially before we were dragged across the Atlantic to where-ever; to know that we came from great civilisations that stood for thousands of years before Europeans saw any light of day. This is what he was teaching as part of his 'groundings' in Jamaica. He wasn't only teaching but learning from Rastafarians – that beleaguered group who are still scorned in our societies. Rodney expressed gratitude for the exchange of knowledge and experiences he gained from grounding with his Rasta brothers (and no doubt sisters too!):

“I would like to feel perhaps that what I am saying in one form or another will reach the brothers and therefore it is a message both to you and to them. And above all, I would like to indicate my own gratification for that experience which I shared with them. Because I learnt. I got knowledge from them, real knowledge. You have to speak to Jamaican Rasta, and you have to listen to him…and you will hear him tell you about the Word. And when you listen to him, and you can go back and read Muntu, an academic text, and read Nomo, an African concept for Word, and you say, 'Goodness the rastas knew this, they knew this before Janheinz Jahn. You have to listen to them and you hear them talk about Cosmic Power and it rings a bell, I say, but I have read this somewhere, this is Africa. You have to listen to their drums to get the Message of the Cosmic Power” (p.82). Of course the authorities feared the swell in consciousness about this 'Cosmic Power' that ordinary people possessed – for this would challenge their right and means to govern them. It was this revolutionary spirit they sought to stymie by banning Rodney. They knew, however, that this power had been there all the time.

Now imagine Dr Walter Rodney, a University of the West Indies lecturer at the time, being humbled by ordinary people in the hills and gullies of Jamaica? What statement was this making about the order of society? He was teaching the people that the power lay within them – this power was not simply about material wants and needs. It is “Cosmic” – meaning boundless and capable of transmuting any circumstance if properly understood and nurtured. Rodney was therefore grateful for the humility experienced from reasoning with the ordinary people (Rastas):

“And when you get that…you get humility, because…you are learning from them. The system says they have nothing, they are the illiterates, they are the dark people of Jamaica. Our conception of the whole world is that white is good and black is bad, so when you are talking about the man is dark, you mean he is stupid. He has a dark mind. So that is what the system says. But you learn humility after you get into contact with these brothers…I find my colleagues, my so-called peers, white people, black bourgeoisie all frustrate me and I get annoyed. I find it difficult to conduct a discussion. I am more likely than not to tell them a few bad words after a while…but with the black brothers you learn humility because they are teaching you” (p. 82). I would venture that not many academics or black middle class would wish to 'learn' let alone believe it possible from the ordinary souls in the street. That is perhaps with the exception of those revolutionaries that understand that power comes from the people. Neo-colonial governments know this too well. But everyone wishes to get ahead or be 'the head' rather than grow and learn from the feet that form the foundation.

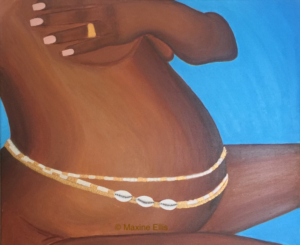

In his reflections in Groundings Rodney acknowledges the beauty in bottom up struggle, which he expressed as the powerful mark of the survival of black people despite our history of being “subjected to genocidal practices” where 'millions' were 'raped' from West Africa by a “system designed to kill people.” Along with humility he says “you get confidence” from the brothers (ordinary people);”confidence that comes from an awareness that our people are beautiful. Beauty is in the very existence of black people” he says (p.83).

And of course the concept of realising the beauty of black people was part of the Black Power Movement, one of whose greatest proponent was Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael). Here again Rodney passionately exposes the government of Jamaica as deliberately trying to undermine the movement:

“They will ban people from coming to the country like James Foreman, Stokely Carmichael. They will ban the literature of Malcolm X, Elijah Mohammed, Stokely Carmichael. The black Jamaican government, in case you don't know have banned all publications by Stokely Carmichael, Elijah Mohammed, all publications by Malcolm X.” This was clearly vexing for Rodney – especially as one of his ambitions at the time was to have a department of African History at the University of the West Indies, where said literature from his point of you would be required reading. The Jamaican government, and we might extend this to all the neo-colonial governments and governors we know wanted what the white imperialists wanted – to keep black masses ignorant of their history, culture and ways they could overcome their dire conditions. The Black Power Movement was inspiring generations – especially young people – it was indeed a young people’s movement. The Rastafarian movement was gaining momentum and culture would be the bedrock of liberation. The Jamaican government wanted a stratification of society in which the masses remained impoverished in every way with the middle classes and intellectuals feeding them culturally and economically disenfranchising fodder. How has this changed? How do contemporary black intellectuals see themselves in relation to the experiences and struggles of the masses, especially in response to continuing forms of state repression?

When he later returned to Guyana, Rodney was fated to experience the same rejection by the Guyanese government who prevented him from working at the University. His assassination in 1980, which the Commission of Inquiry (2016) called for by the Walter Rodney Foundation into his death, concluded was state led under the Forbes Burnham government. This killing equally lead to a loss in the opportunity to expand the depth of politicisation rooted in our diverse cultural experiences. It is a travesty that the Report from the Commission of Inquiry has received no validation from the present coalition government lead by David Granger. Consequently, not many Guyanese, especially the young do not know anything about Rodney, his scholarly work and ultimately his readiness literally to meet people where they were in order to use his knowledge to elevate theirs.

Though the banning of Rodney took place in 1968 and his assassination in 1980, he must have been a marked man long before then. His Marxist ideology and condemnation of capitalism during a period of hyper anti-communist propaganda by Western imperialists like the Unites States of America would naturally have identified him as radical, revolutionary and a rebel to be watched. Long before then the fear that Guyana would follow Cuba and become a communist nation caused Britain to suspend the constitution following Guyana’s elections in 1953. They replaced the self-professed communist Cheddi Jagan with Forbes Burnham whose brand of ‘socialism’ was just that – a brand that didn’t quite challenge those Western powers as much as Rodney’s call for ethnic unity in Guyana seemed to challenge Burnham.

These “groundings” or “reasoning” – as I knew this concept from overhearing conversations between my brother and his friends over trails of ganga smoke when I was younger were for Rodney a counterpoint to the formal lectures he gave at the University. For this reason he implored black intellectuals to “attach [themselves] to the activity of the black masses” for the social and cultural enrichment that this grounding would provide (p.77). I wonder where we might we be if every black intellectual was prepared to forego the privilege afforded them in society and abandon the prerequisite of ‘joining the establishment’ (76) as Rodney did. What if they were prepared to go to the gullies and ‘dungles’ and to the ‘rubbish dumps’ where the people are forced to live out of poverty? What if that particular class saw their responsibility the way Rodney did – and wanted ‘to contribute something’ of what they had learnt about life not just to the willing students who populate University campuses but to those who didn’t have those kind of opportunities? Successive governments would have to ban them without end. But the responsibility to give back the way Rodney saw it would have phenomenal impact, were those intellectuals prepared to organise with the masses, bringing conferences to the people in the “low places” too so that those governments that crush rebellions and kill revolutionaries would find it impossible to also kill those ideas with each one teaching one and saying that ‘I too am Walter Rodney.’

October 16th 2018